A 'Box' of Different Number Ones

HIGHER GROUND IN THE OTHER TRADE WEEKLY

Exactly how many No. 1 Motown singles on the pop charts does, say, Stevie Wonder have to his credit?

Well, it depends. According to the so-called bible of the music industry, Billboard, the total is eight. The first was 1963’s “Fingertips (Pt. 2),” the last was 1985’s “Part-Time Lover.” But if you refer to the industry’s other primary chart source of the period, Wonder went to the mountain top no fewer than 14 times. Hits of his which stopped short on the Billboard Hot 100 – such as “For Once In My Life” and “Higher Ground,” to name but two – reached No. 1 on the Cash Box Top 100.

The disparity doesn’t stop there. Smokey Robinson never gained a solo No. 1 pop single in Billboard, but earned two in Cash Box. The Jackson 5 reached the summit in both trade publications with their first four Motown 45s, but earned another three in Cash Box. Their Billboard total remained at four.

Cash Box cover stars, with seven No. 1s

Gladys Knight & the Pips never topped the Billboard Hot 100 while at Motown, but travelled twice to the peak in Cash Box. The latter also bestowed No. 1 honours on R. Dean Taylor and the Undisputed Truth, and on “What’s Going On.” That’s right: Marvin’s signature song of the ’70s stalled at No. 2 in Billboard.

West Grand Blog readers will likely be familiar with both trade papers, and with the differences between their charts – not only the pop listings, but also the R&B rankings. And although Cash Box went out of business more than 20 years ago, its best-seller lists, as well as its editorial coverage, qualified as essential reading during Motown’s heyday.

Both Billboard and Cash Box were “integral pillars of the independent record era,” confirmed John Broven’s definitive Record Makers and Breakers tome. Both weekly magazines compiled influential singles and LP charts with data from similar information sources: jukebox operators, music retailers, one-stops and rackjobbers

“When I joined Cash Box in 1959, it was simple,” said Mike Martucci, who ran its research unit for many years. “The basic concept of Cash Box was a trade publication for the coin machine industry, for jukebox operators in restaurants and diners and the like. But I remember meetings with some of the coin operators and they said, ‘The charts you’re giving us, they’re kind of late, we’re not getting the current stuff.’ ”

And so Cash Box dug deeper: record retailers, distributors and wholesalers. “As we increased our research at retail,” continued Martucci, “we were told, ‘You’re still not there.’ So we spent more time finding the key mom-and-pop record stores as well as the largest retail accounts. It seemed to work. Then as time went by, radio became more aggressive [in playing new music] and we were a little behind. Radio would start a hit song first, so we looked at the key stations. We went after Top 40 stations, because we were concerned about the main chart, the Top 100. But once you get to a certain level, there’s always more you can do.”

During our conversation earlier this month, Martucci remembered the call-out process (“We used different coloured pens to write down the information from different types of accounts”) and the weighting system. “A big rackjobber might be worth ten points, a distributor in Chicago might be eight, and one in South Dakota, four.”

The chart differences between Cash Box and Billboard was often attributed to data collection. “When we had a particular song at No. 1, maybe it got a higher percentage of accounts reporting to us,” said Martucci. “There were no computers, we just went by the numbers from our sources during a given week. Did we get a particular Chicago distributor? Did we get that rackjobber out of Michigan? It was the best system available at the time. No one had all the answers.”

Meanwhile, being a chart-reporting outlet meant that record companies large and small, major and independent, provided plenty of incentives for those retailers, one-stops or rackjobbers to fulfil their obligation promptly, fully, generously.

The Motown maestro with the strongest trade-paper relationships during the ’60s was vice president Barney Ales, not least because he knew Billboard publisher Hal Cook from when both worked at Warner Bros. Records. Taking advertising space gave record companies leverage, or at least consideration, when it came to chart positions, he said. “You could get what you wanted if you bought an ad.” Ales became well-acquainted with Billboard research director Tom Noonan, and later recruited him to Motown. Ales also knew Cash Box publisher George Albert; at one point, the two were neighbours in Los Angeles’ Encino suburb.

THE BEST SEATS IN THE HOUSE

For most of the 1960s, Motown’s No. 1 singles were usually the same in both magazines – but not always. The Detroit company’s first on the Billboard Hot 100 was “Please Mr. Postman” in 1961, while on the Cash Box Top 100, it was “Fingertips (Part 2)” in 1963. “My Girl” went to the top in Billboard in ’65, but not in Cash Box.

According to Martucci, Motown paid more attention to the charts – and which accounts reported what records – when its artists began gaining regular exposure on network television and appeared at nightclubs such as New York’s Copacabana. “When you got booked at the Copa, you’ve made it,” he said.

In turn, this increased perks for the trades. “We were guests to see these artists, given the best seats in the house,” said Martucci. “Motown people would fly into New York, and we became good friends. They started ‘working’ the trades, they advertised more, they had more stories to tell our editors. But it wasn’t some guy walking in with hundred-dollar bills. That wouldn’t work.

“The label guys would come up to our offices every week with the information about their latest songs. On Tuesday mornings, it was like a doctor’s office: ‘Next!’ We took it all with a grain of salt.” But there were lively conversations, confirmed Martucci, if a single made it to the top of one magazine’s chart, and not the other. “They would put on the pressure.”

For his part, former Cash Box editor-in-chief Irv Lichtman doesn’t remember major clashes involving No. 1 singles on the competing charts. “The pressure really built up,” he told me recently, “when we introduced the red circle – the “bullet” – on movements of at least ten places.”

Martucci elaborated: “People in the industry wanted something to make our research more effective – when, for instance, a record went from 35 to 19. We were asked whether we could do something to make [the progress of] a song more memorable.” Cash Box music editor Marty Ostrow explored options with the printer, including adding a black dot for fast-rising hits. “Marty was told, ‘We can do any colour you want – and, by the way, we call it a bullet.’ So we introduced the red bullet on our charts in 1959.”

A BLACK BULLET FOR THE OTHER DIRECTION?

Naturally, there were consequences. “One of the really negative aspects of a bullet was the pressure from labels to get one,” said Lichtman. “As the years went by, movement up the charts [by] less than ten positions got the reward. I think the qualification was being close to the rarified Top 10.” Lichtman also recalled “a whimsical discussion on giving a black bullet to singles dropping the most in a given week.”

Despite their rivalry, relationships between the staff of both magazines were cordial. “I was friendly with a number of their editorial and ad folks,” recalled Lichtman, “especially Ian Dove and the great Mike Gross. Bob Rolontz and I liked each other, but occasionally tussled over an arrogance on his part about Cash Box’s less-than-stellar editorial independence – although Billboard wasn’t exactly winning Pulitzer prizes, either. The music industry trade paper syndrome! Maybe it’s partly due to the fact that we all loved music and so many people in it.”

Cash Box's Mike Martucci (second left) and Anthony Lanzetta with Mary, Jean and Cindy of the Supremes

The Cash Box and Billboard chart-peak differentials became more obvious towards the end of the 1960s and into the next decade. “I knew the people who did the research at Billboard,” said Martucci, “but we never exchanged information.” One view is that Cash Box owner Albert was reluctant to make major investments in data-collection technology in the ’70s; he seemed more interested in moving the magazine to Los Angeles.

Regardless of all this, the differentials make interesting reading for chart buffs and Motown pilgrims – although it’s clear that, in both papers, 1970 was Hitsville’s best year for No. 1 pop singles. There were seven of those in Billboard, and ten in Cash Box.

The respective charts also gave the Supremes the same career total of No. 1 hits – twelve – although when it came to the group’s 1969 duet with the Temptations, Cash Box took that to the top, and Billboard did not. Finally, both magazines agreed that the last best chart year for Motown under Berry Gordy’s ownership was 1985, when two titles went all the way: “Part-Time Lover,” as noted above, and “Say You, Say Me” by Lionel Richie.

So here’s the data: the 22 singles from Motown Records which claimed the peak of the Cash Box Top 100, but not of the Billboard Hot 100. After the year/title/artist for each record is (in parentheses) the number of weeks at No. 1. Below that is the date of its Cash Box conquest, followed by the chart peak in Billboard. Sure, it’s what’s in the grooves that count(s), but numbers are illuminating, too…

1968: “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS (1)

Jan. 13 (Billboard: 2)

1968: “For Once In My Life,” STEVIE WONDER (1)

Dec. 14 (Billboard: 2)

1969: “I’m Gonna Make You Love Me,” DIANA ROSS & THE SUPREMES & THE TEMPTATIONS (1)

Jan. 25 (Billboard: 2)

1970: “Ball of Confusion,” THE TEMPTATIONS (1)

July 25 (Billboard: 3)

1970: “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours,” STEVIE WONDER (1)

Aug. 22 (Billboard: 3)

1970: “Indiana Wants Me,” R. DEAN TAYLOR (1)

Nov. 14 (Billboard: 5)

1971: “Mama’s Pearl,” JACKSON 5 (1)

March 6 (Billboard: 2)

1971: “What’s Going On,” MARVIN GAYE (1)

April 10 (Billboard: 2)

1971: “Never Can Say Goodbye,” JACKSON 5 (1)

May 29 (Billboard: 2)

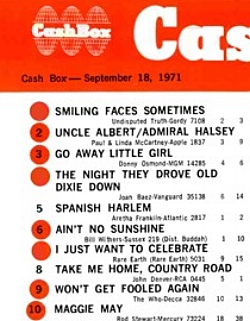

1971: “Smiling Faces Sometimes,” THE UNDISPUTED TRUTH (1)

Sep. 18 (Billboard: 3)

1972: “Got To Be There,” MICHAEL JACKSON (1)

Jan 1 (Billboard: 4)

1972: “Rockin’ Robin,” MICHAEL JACKSON (1)

April 15 (Billboard: 2)

1973: “Neither One Of Us,” GLADYS KNIGHT & THE PIPS (1)

April 7 (Billboard: 2)

1973: “Higher Ground,” STEVIE WONDER (1)

Oct. 13 (Billboard: 4)

1974: “Boogie Down,” EDDIE KENDRICKS (1)

March 1 (Billboard: 2)

1974: “Dancing Machine,” JACKSON 5 (1)

May 18 (Billboard: 2)

1975: “Boogie On Reggae Woman,” STEVIE WONDER (1)

Feb. 8 (Billboard: 3)

1979: “Sail On,” COMMODORES (1)

Oct. 20 (Billboard: 4)

1980: “Cruisin’,” SMOKEY ROBINSON (1)

Feb. 16 (Billboard: 4)

1980: “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” STEVIE WONDER (2)

Dec. 6/13 (Billboard: 5)

1981: “Being With You,” SMOKEY ROBINSON (1)

May 23 (Billboard: 2)

1982: “That Girl,” STEVIE WONDER (1)

April 3 (Billboard: 4)