A Tale of Two Smogs

INSIGHTS AND INTERVIEWS, WITHOUT CHAPERONES

The most prolific rock biographer of the past 40 years may well be Philip Norman. This English author has delivered substantial books about the Beatles and the Stones, McCartney, Lennon, Jagger, Buddy Holly, Elton John and Eric Clapton. The last of these, he declared after its publication, “left me feeling more than ever that writing books about such people is no job for a grownup.”

Norman also conducted one of the first major-newspaper interviews (albeit brief) with Berry Gordy, published 51 years ago. Up to then, the Motown founder had yielded his time to a relatively few journalists in America, let alone a Brit.

“Gordy himself in no way resembles the dynamo, the almost mystic judge of a record’s potential that his employees say – and history proves – that he is,” wrote Norman for Britain’s Sunday Times. “He turns out to be a small, faintly hunched, bearded, watchful man in his early forties; watchful in the sense that, after a perfectly innocent question, he will stare at the questioner as if he suspects anarchy and plagiarism in it.”

Cindy shines for the Sunday Times

The eight-page cover story for the paper’s prestigious weekend magazine was entitled “Black Gold: The story of the Motown millions,” and it appeared on February 14, 1971. The record company had just completed a year in which it secured seven Number Ones on the Billboard Hot 100 – the most in its history – while in Britain, it achieved 15 Top 10 singles and reigned over the album best-sellers with two volumes of Motown Chartbusters.

The 4,400-word piece was neither as snarky as the above extract suggests, nor as bland as Motown itself usually preferred. “It was arranged,” Norman told me a few years ago, “through Burson-Marsteller, an Americanised British PR firm, who said, ‘That’s fine, you can go out and talk to whoever you want.’ ” The journalist journeyed to Detroit and Los Angeles, and for the most part, was not chaperoned in either location. “I would just go along and be let in.”

When read today, the narrative in Norman’s article is familiar, but there are a number of enduring insights – and at least one mystery. As well as Gordy, he interviewed Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, Cindy Birdsong and Levi Stubbs. He spent time, too, in the company of backroom believers – Phil Jones, Jim White, Junius Griffin – and songwriters Pam Sawyer and Gloria Jones, plus Quality Control queen Billie Jean Brown.

The artists were quoted throughout, but not at length; Ross earned the most column inches, but not the magazine’s cover, surprisingly. “The rehash of Mafia connections was a bit of old news, and not one that ‘we’ wanted to be continuously repeated without any factual truth,” says John Marshall, Motown’s London-based international director at the time. “But I suppose to a journalist that wants to get their ‘pieces’ noticed, it was always going to be included. Factually, Philip got a lot right, but a lot was inevitably going to be just a brush over the surface.”

Norman himself commented to me about “the utter wastefulness of sticking all those interviews in one article,” yet at that point in the early 1970s, national newspapers – on both sides of the Atlantic – simply did not devote the space to popular music, and its business aspects, which they later came to do.

A FEW ‘SACRAMENTAL’ MINUTES

Half a century on, “Black Gold” doesn’t appear to be widely accessible online, except by subscription to Rock’s Back Pages, although physical copies of the magazine can be found on eBay or the like. So here, then, is a selection of edited excerpts (in italics), followed by Philip Norman’s recollections, and one or two other comments.

I was permitted a sacramental few minutes with [Berry Gordy] at his Los Angeles office. That the company is now directed from Sunset Boulevard instead of Detroit is taken as further evidence that the mobs are in control – yet to have ambitions in films and television, as Motown does, and not to be at the West Coast would plainly be unwise. Also, nobody can blame the Motown Supreme Command for preferring the brighter of the two smogs.

Suited-and-booted Jim White (left) and non-violent revolutionary Junius Griffin

“I was allowed to talk to him,” reiterated Norman when he spoke to me, “but he was surrounded by a lot of rather cold-eyed white blokes, and looked at me suspiciously all the time. My innocent badinage probably did not go down very well. But at least I did see him.”

At the West Coast, Gordy's immediate deputy is Jim White, formerly a lawyer at the influential William Morris theatrical agency, and a man of cobra-like calm. “I've had what you would say was a classical education – Stamford, clerkship in the Supreme Court of California; before I came to Motown I was offered a vice-presidency at Columbia Pictures – and I'm just one of Berry's fingers.”

White, a little-known figure in Motown history, was vice president of Motown Productions, Inc., who was appointed in 1971 and got to announce the making of Lady Sings The Blues, the film’s $5.5 million budget, and Diana Ross’ casting as Billie Holiday. “He was a smart, kind of casual, youngish white guy, who wore suits,” Chris Clark told me recently, “and I think he helped smooth the path between Motown and Paramount.” Clark should know: she was co-writer of the Oscar-nominated Lady Sings The Blues screenplay.

White's close associate is the Motown Press Director, the bearded Junius Griffin. His former occupation was helping to write the speeches of the late Dr. Martin Luther King. Griffin also has to write Gordy's speeches with the right sort of plum in the mouth; and he has been put in charge of Motown's first serious attempt at black politics, an issue of albums of the speeches of Stokely Carmichael, Dr King and other dissenters. “Music,” Griffin says, “is the only form of communication – revolutionary communication – that is non-violent.” With a canyon-top bungalow and access to hundreds of free records, it is a style of revolution that appears to suit him.

OF DR. KING, AND SHORTY LONG

Evidently, Norman was unimpressed by Griffin, and on later reflection, he described him as “quite obnoxious.” Yet the former Marine was a Motown employee with the most knowledge of America’s civil-rights struggle, having reported on it extensively for the New York Times and Associated Press, before joining the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where he worked with Dr. King. His third wife, Ragni Lantz, was a journalist who covered Washington politics for Jet magazine – and who penned the liner notes of 1969’s The Prime of Shorty Long album.

Another of Gordy's innovations – which has since lapsed – was a school within Motown to instruct his artists in manners, posture and deportment. One of the charm school's failures, according to a Motown writer, was a fat girl named Oda Barr. “She was in Vegas and they had the tapes on her in Detroit and went wild about her. They brought her up here [to Los Angeles] and she weighed like 240 pounds but still they put her on a diet, they even sent her to reduction parlours. Then one day someone was sent up to the hotel to her and in her room she had ... a whole box of Hershey bars. She ate herself right out of that contract."

Barney Ales introduces Philip Norman to Motown’s Detroit stockroom

Barr seems to be a near-invisible Motown figure, despite the waistline. The only intel about her appears to be that quoted above, which was repeated in Gerald Posner’s book, Motown. Barr might have been mistaken for Oma Heard, another singer who recorded for the company but had little released. A photo of generously-proportioned Heard (under her married name of Drake) adorned the cover of a 1982 gospel album by the LaVerne Ware Singers. The group’s name matches that of Gloria Jones’ songwriter pseudonym, about which there’s more below.

Office conditions generally are quite horrible: some floors are fitted with corner mirrors of the type that discourage shoplifters in supermarkets; the only employee-catering is by a dire little automat…and only the most select offices are equipped to make telephone calls to numbers outside the building. The lifts are ancient, cage-clanking devices passing by; with musicians in them they look like miners' cages on their way down to some impossible masquerade.

Norman was describing Motown’s downtown headquarters in Detroit (“its artistic capital”). His host at the Woodward Avenue site was sales director Phil Jones, “an amicably flaccid white man in a frilled shirt, somewhat resembling a Country-and-Western disc jockey of yesteryear.” He quoted Jones as saying, “Berry works with a rifle and not with a shotgun, hitting the target in one, not slinging pellets at it, hoping to hit it.” Norman added for me, “Before I even knew about Motown, I always thought those records sounded like jackhammers.”

The Motown Spinners had just had their first real hit with “It's a Shame” – so they were still humble enough to be appearing locally, in a bar called Casino Royale in the city's North-West section (Detroit seems more brooding and miserable than perhaps it really is because it lacks warm-sounding suburb names). The Spinners have been in the company for years, famous principally as imitators of other Motown artists. On this night they even did an unkind impersonation of Stevie Wonder's blindness and it was warmly applauded by a crowd that remained attentive even in the brief instant when a fight broke out and someone flew dizzily along the surface of the bar.

THE ‘ODD JOB MEN’

The Spinners’ imitation of other Motown acts was “very subversive,” in Norman’s opinion. “One of them told me they had to be pallbearers at some funeral in Detroit. They were like the odd job men.”

[Pam Sawyer] sat upstairs in the Detroit building with her latest collaborator; a little black girl called Laverne whose hair was so frizzed out at the sides that she seemed to have placed her head between the paws of a gigantic bear. They had co-written a song called “I Can't Forget The One I Love.” Pam Sawyer produced the lyric, and the music and test vocal came from Laverne; so did the best line: “I can't forget you/Not even the size of your shoe.” “It came from a guy I knew once,” Laverne said. “He had tennis shoes, kinda' ree-al raggity.” Pam Sawyer was cautious. “I'm worried,” she said, “about that ‘whoo-hoo’ bit. They'll say, ‘It isn't Motown.’ ”

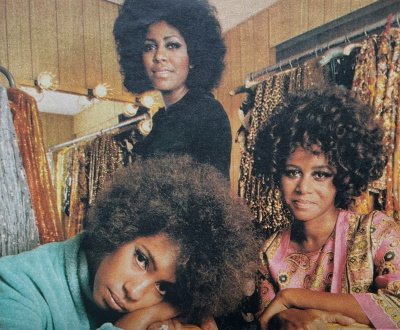

Mary, Jean and Cindy pose for the Sunday Times

The “little black girl” mentioned above was none other than Gloria Jones, who wrote songs with Sawyer under the name LaVerne Ware (her life as a singer may not have been shared with Norman). And shortly before the journalist arrived in Detroit, what proved to be frizzy-haired LaVerne’s most popular song (co-written with Sawyer) was recorded there by Gladys Knight & the Pips: “If I Were Your Woman.” The following year, it was Grammy-nominated.

Looking back, said Norman, the whole assignment amounted to “amazing access” to a company which was reshaping the music industry. At one point, he was able to “sort of sit around with all these people and hear them talk to each other, and not have to interview them.” Yet time spent with, say, Billie Jean Brown (“a perfectly ordinary, middle-aged black woman”) yielded nothing more than an admission that she had held up Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” for two years.

Whatever the post-publication verdict about “Black Gold” within Motown, Norman was not denied further access to its stars. A subsequent feature about Stevie Wonder in the Sunday Times came with no publicists monitoring every word. “His brother, Milton, let him out of his hotel in New York, and I was going to drive with him to Philadelphia,” Norman remembered. “Milton said, ‘Would you mind looking after Stevie?’ I led him around for the rest of the day and into the evening. He was so completely charming that I worried about leaving him that night.”

It’s a shame that Philip Norman didn’t use that unusual opportunity as the foundation stone for one of his well-regarded biographies. It could have been still more “Black Gold.”

Book notes: Philip Norman’s own memoir, We Danced On Our Desks, is due this December. According to Mensch Publishing, it will be “a vibrant cultural insight into the ’60s and early ’70s and his own incredible experiences.” Even if it wasn’t a job for a grownup.