The 'Fingertips' Man

‘BEANS’ TRANSCRIBES FOR JONI, TAKES A HIT FOR HONESTY

In my dreams, I’m ghost-writing Stevie Wonder’s autobiography. So now it’s time to interview the individuals who were involved with his earliest years at Motown: Ronnie White, Clarence Paul, Ted Hull and Thomas “Beans” Bowles, to name but four.

Wait, you say: most of those have gone to join the choir invisible. Ah, yes, I reply, you’re right, as I snap out of the reverie.

Beans at the Frolic (with typo) and free parking

Even so, the name of the late Beans Bowles has resurfaced recently in an unexpected context – that of the work of Joni Mitchell. Joni on Joni is a new book by esteemed Detroit journalist Susan Whitall which draws together “interviews and encounters” with the Canadian singer/songwriter, covering all aspects of her life and her music. It includes details of her time in the motor city, after she married folk singer Chuck Mitchell and lived with him there from 1965-1967.

“Such early songs as ‘Both Sides Now’ and ‘Circle Game’ sound as if they were written under endless prairie skies, or in hippie California,” Whitall told the Metro Times a few weeks ago, “but it was in a gritty Detroit that Joni scribbled their lyrics in a coffee shop.”

Equally revealing is the fact that Chuck Mitchell’s friendship with local lawyer Armand Kunz led to music publishing being set up for Joni, so that she would benefit if and when other singers were drawn to her work. “It was important for her to be able to be paid by people when they covered her songs on records,” said Whitall, “and that’s what launched her.”

TRUDGING UP THE STAIRS

And what of the Motown connection? “Chuck said that he sought out someone to write lead sheets for Joni’s songs,” explains Whitall in Joni on Joni, “and he found a musician he describes as a lean six footer, ‘definitely from Motown, African American, fortysomething, a reed man,’ which fits the description of flutist/saxophonist (and, for a time, Motown bandleader) Thomas “Beans” Bowles. The ‘reed man’ trudged up the stairs to their bohemian pad, Chuck remembered, but was skeptical of Joni’s unusual tunings until he watched her hands on the guitar and found himself caught up in the melodies.”

Bowles – assuming it was he – understood melodies. This six-foot-four, stringbean-thin jazzman from South Bend, Indiana, had been navigating them for years in Detroit before stepping into United Sound in late ’58 to back Marv Johnson singing “Come To Me” for Tamla 101. Bowles had fronted a band at the Frolic Show Bar on John R. Street, playing behind the likes of Wynonie Harris, the Four Tops, Clea Bradford (Janie’s sister), Pee Wee Crayton and Frances Burnett; then, he gravitated to Maurice King’s crew at the nearby Flame Show Bar.

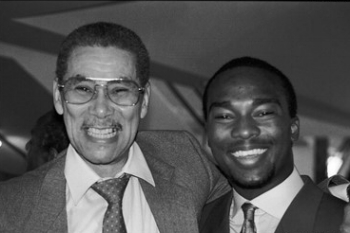

Beans in the ‘90s, with rising sax star James Carter (photo: W. Kim Heron)

That Bowles would join Berry Gordy’s upstart business was surely inevitable; that he had organisational as well as musical skills, perhaps less so. After a spell as Marv Johnson’s road manager, he returned to Hitsville to play on records and to guide youngsters there, including Little Stevie Wonder. (It was Bowles who played the dizzying, dynamic flute on the original, studio version of “Fingertips.”) As assistant to Esther Edwards, he advocated for the idea of a Motown roadshow, a caravan of stars in concert for the audiences who were buying the hits.

Bowles is one of the backroom believers who earned his place in music history. There’s hardly a Motown autobiography which doesn’t mention him with affection, and several of them offer a real sense of his personality. My favourite anecdote is in Martha Reeves’ Dancing In The Street, when Bowles was supervising the first Motortown Revue as it swung up and down the eastern seaboard during the autumn of 1962. Reeves and Mary Wilson were sharing a hotel room one particular night, and had gone to bed early, ahead of an arduous journey. “As soon as we drifted off to sleep,” Reeves writes, “we heard a frantic knock on the door, and as we woke up, the door flew open, the security chain breaking loudly. Mary and I, scared out of our wits, sat up in bed, our hair in rollers and head rags.

SHINING A LIGHT

“There in the doorway stood Mr. Thomas ‘Beans’ Bowles, with flashlight in hand, turning the beam from one face to the other, searching the room. “Okay, where are the men?” I answered him sharply, “Yeah, that’s what we want to know! Where are they?”

The more familiar tale from ’62 is that of the fatal car accident involving Bowles and assistant Eddie McFarland. In To Be Loved, Berry Gordy notes that it took place after the Revue’s November 21 playdate in Greenville, South Carolina, as the two men were en route to the next show, in Florida. Their vehicle collided with a truck, seriously injuring both. Bowles was in good spirits when Gordy visited him in hospital; McFarland subsequently died.

Little Stevie plays for Dennis and Harold Bowles outside Hitsville U.S.A., 1963

“Beans had lost $12,000 in gate receipts that he’d had on him,” he recalled. “But when the Highway Patrol found the car, they also found the money and returned it to us. With relief, we realised that just because it was the South didn’t mean all white people were bad.” The Motown founder, with Esther Edwards, subsequently took over for Bowles and MacFarland on the Revue, noting in his book that he had “no idea how much work went into handling these shows.”

Yet these stories are in sharp contrast to the depressing tale of Bowles’ involvement in the politics of the Michigan township where he lived, Royal Oak. This dark episode appears in Dr. Beans Bowles – Fingertips: The Untold Story, authored by Bowles’ son Dennis, and published in 2003. The book includes what appears to be the complete transcript of a statement given to county prosecutors by Beans in April 1965, when he was on Royal Oak’s board of trustees. He spoke of efforts to bribe him for a vote in favour of a particular property development. He had gone to the police, but this honesty apparently resulted in threats to him and his family. “The police were guarding our house night and day,” wrote the younger Bowles. “We went to church and the white officer sat in the choir loft as we sang with the choir.”

Royal Oak had form in this regard. “Political scandals have racked the township of 8,000 residents periodically for 25 years,” reported the Detroit Free Press in June 1965, noting “widespread crime and corruption” there. When Bowles gave his statement to prosecutors, he had only just returned from the U.K., where he played a key role in managing the Tamla Motown tour.

A THREAT TO BLOW UP MOTOWN

Bowles’ entanglement in the bribery case led to a nervous breakdown for his wife Agnes, and worse. He was fired from Motown, wrote his son, “because of his political aspirations. Berry called him in the office one day and sat him down to talk. Berry informed my father that the mob had threatened to blow up Motown if Berry didn’t get rid of him. [Gordy] said, ‘I love you, Beans, but I can’t risk everybody in the company for you. I’ve got to let you go.’”

A book for Motown completists

No other Motown book gives an account of this shocking fate. According to Dennis, his broke, jobless father was eventually able to secure employment at Detroit’s 20 Grand through the efforts of Hitsville bandleader Earl Van Dyke. “As time went by, time healed all wounds,” the son writes. Around 1971, Smokey Robinson hired Bowles as his musical director for work on the road, a post he held for several years. He also worked with the Four Tops, and later went into business with Dennis and his other son, Harold. The Three Bee’s Production Co. presented a variety of music shows in and around Detroit, including one in 1974 with pre-rock & roll star Al (“Unchained Melody”) Hibbler and former Motown artist, Singin’ Sammy Ward.

Bowles continued to toil in his sixties, with a stint as an actor in a Detroit production of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom – in the cast, too, was Earl Van Dyke – and leading the band in another play, Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1992, and the following year, a number of musicians and singers staged a tribute show for him. Among them were the ladies whose room he had burst into 31 years earlier, policing forbidden liaisons: Martha Reeves and Mary Wilson.

Bowles succumbed to prostate cancer on January 28, 2000. He was 73. “This is a celebration of an angel on Earth,” Stevie Wonder told the standing-room-only crowd at the Central United Methodist Church in downtown Detroit, paying tribute to the man forever known by his nickname. “It is also a celebration of a true spirit and a griot. For me, he was a teacher and also a father.”

And dreams? It’s a fair bet that Thomas “Beans” Bowles inhabits Stevie’s once in a while.

Music notes: as noted above, Beans Bowles’ masterful flute can be heard on Marv Johnson’s “Come To Me” and Little Stevie Wonder’s instrumental “Fingertips,” both available on streaming services. The latter track opens The Jazz Soul Of Little Stevie, with Clarence Paul and Hank Cosby credited as writers; Bowles arguably deserved a piece. He recorded material in 1962 for his own album on Workshop Jazz, but it was never released. However, seven tracks from those sessions became available digitally in 2012, and can be found on Motown Unreleased 1962: Jazz, Vol. 2.

Book notes: Susan Whitall’s Joni on Joni was published by the Chicago Review Press last month in hardcover and digital editions. Dennis Bowles’ book about his father is available in paperback and digitally. Beans can be seen and heard in various video clips, notably from the WGBH archive and the Detroit Sound Conservancy. He was also interviewed for the definitive book about the Detroit jazz scene, Before Motown, by Lars Bjorn with Jim Gallert. This includes details of Bowles’ career and his invaluable recollections of the city’s music landscape during the 1950s.