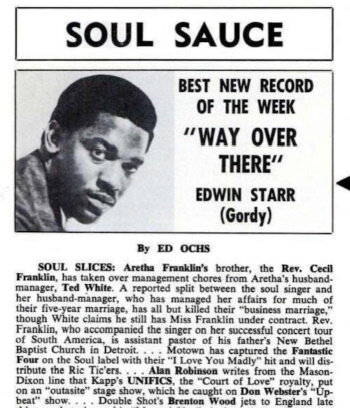

A Weekly Diet of Soul Sauce

AN UNUSUAL ‘INITIATION’ FOR BILLBOARD’S R&B EDITOR

Jerry King, deejay at the Arthur discotheque, is still talking about David Ruffin of the Temptations, who sat in with the Arthur band, the Fuzzy Bunnies, and was just something else. The Temps made the club since they were in town anyway, mixing up thousands of minds at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. The group’s new LP, Wish It Would Rain, is out – and out of sight. The cover photograph, shot for the Temps date on the Rowan & Martin Laugh-In, shows the group on a desert – in Hollywood, that is. The desert is really the man-made mountains of a cement company.

This was the opening of one of the first Soul Sauce columns written by Ed Ochs, Billboard’s then-new R&B editor, in the issue dated May 18, 1968. What it described was an example of why the magazine became my bible: inside information about artists I revered, insights into people and places, and, in this instance, a revelation (one which Motown was hardly likely to publicise) about the cover art of a new album.

Parched in a desert of Hollywood cement

Billboard also represented fuel for Groove, the weekly Motown newsletter that I wrote for the record shop which then employed me. This two-page missive was sent free of charge to our regular customers, containing news about Motown’s latest U.S. and U.K. releases, its weekly presence on the Billboard Hot 100, concert reviews, and snapshots of select singles and albums from the past. And there at Groove’s runout (“Tamla Tailpieces”) for that week in May ’68 was a precis of Ed Ochs’ item about the Temptations in New York, who “went down a bomb…good on yer, Dave!”

Motown’s magnificent Martha Reeves, apartment-hunting in New York, stopped to swap talk with Soul Sauce last week, ending all rumors of a split with Motown. The Vandellas, reshuffled to keep the unit of the group, will soon hit the road and recording studio to keep the soul sounds rolling. The group’s latest record, “I Can’t Dance To That Music,” was the sore spot between Martha and Motown, when her voice was dubbed over with a Diana Ross sound-alike.

Thus wrote Ochs, resuming Soul Sauce duties after a trip to Miami for the annual convention of the National Association of Television and Radio Announcers (NATRA), the black disc jockeys’ organisation. What he did not report in Billboard was an occurrence at one of the convention hotels, when he was “involuntarily escorted from an elevator to a room by people I actually knew…accompanied by a couple of thugs with what clearly appeared to be guns bulging in their shirts. Once in the room, I listened concerned while they debated throwing me out an 11th floor window.” It was only due to the intervention of a respected black promotion woman, Effie Smith, who said, “Oh, he’s alright,” that Ochs was released. “In a strange way,” he said, “I considered that an initiation.”

AN UGLY ATMOSPHERE

Ochs, who was white, had joined Billboard in 1967. As he began writing Soul Sauce the following spring, black militancy was growing and the music industry was feeling the pressure in line with other sectors of American life. Some of that pressure had nothing to do with justice or civil rights. Motown, for one, had encountered the Fair Play for Black Citizens Committee, a dubious group from New York which had been trying to infiltrate radio stations to extort money from record companies. The “committee” muscled into the NATRA event in Miami, and there were assaults and intimidation amid an ugly atmosphere which the association’s officials seemed powerless to halt.

A slice of soul every week

Ochs aside, a number of white music industry attendees were warned to leave the convention, including Aretha Franklin’s producer, Jerry Wexler, and Motown executive Gordon Prince. “I felt uncomfortable,” Prince told me some years ago, “and the whole thing was very tense. In fact, I saw Martin Luther King’s widow coming out of a meeting somewhere, and she was crying.”

More than a half-century later, the author of Soul Sauce has an interesting perspective. “Like what the hell was I doing in the first place, a white R&B editor in a rising black culture revolution,” Ochs said to me recently. “Billboard had no R&B editor in 1967 or before. The magazine was only then poking its nose, if not its head, out of the Jim Crow era. In the 1950s, not too many years before the R&B charts, there were the Race charts.”

When Ochs arrived at the magazine, a black advertising salesman was its editorial contact for R&B, “just because he was black, and Billboard wanted nothing to do with the black music industry,” he said. “So they let him do it, and do it poorly. Black music was driving the business, yet Billboard didn’t want to acknowledge it, didn’t know how, and didn’t want to take the basic steps to find out.” It was, Ochs contended, “a family-owned, ‘white-bread’ magazine riding the country music bandwagon out of Nashville, classical music, and music publishers in New York, but the music world was rapidly changing around them.”

Still, the newsweekly’s editor-in-chief, Lee Zhito, recognised its shortcomings, and decided that in 22-year-old Ochs, he had someone tuned into the ’60s music revolution. “But I was deeply conflicted and concerned about taking a job that clearly should have gone to a qualified black writer, not me. Lee didn’t want to interview anyone else. I felt I had no choice but to take it on. I didn’t want to disappoint him, lose his confidence and maybe my job.”

MOTOWN’S CROSSOVER DOMINANCE

By this time, Motown was firmly in the mainstream of the music business. “Although Billboard’s R&B charts at the time probably weren’t the most accurate reflectors of true R&B record sales,” said Ochs, “its pop charts were still by far the most powerful, irrefutable documentation of Motown’s crossover dominance. Moreover, the company wanted everything that Billboard offered: exposure to tens of thousands of white retailers and pop radio stations, and consequently to millions of white record buyers.”

Ed Ochs with the “new” Supremes

Motown’s sales chief, Barney Ales, had recognised this years before, of course, and had strong relationships with the magazine’s publisher in New York, Hal Cook – they first became acquainted in the late ’50s when both worked for Warner Bros. Records – and Tom Noonan, director of its research department. But charts were Ales’ primary focus, and he had little contact with reporters, Ochs included.

Heavily raw and ragged-voiced with the brogue of a bull soul singer, [Dennis] Edwards ripped into “Ain’t Too Proud To Beg” and “Beauty Is Only Skin Deep,” dragging the classics over a bed of vocal nails. His lusty revival-meeting tactics, a bone in the throat of the Temps’ velvet harmonies, stood out in glaring contrast, stirring up hushed inquiries on the whereabouts of David Ruffin.

Naturally, Billboard was invited to all the important New York shows featuring Motown acts, particularly at the Copa, as reviewed above (in part) by Ochs. “I received all my assignments directly from the talent editor, Mike Gross, who passed them on to me. My focus at that time was largely on talent and product, very little on the business side. I was treated well by Motown, hard news or soft.” He remembered one particular publicist for the firm as “a piece of work, a dour, difficult personality, but you had to hang in with people if you wanted to get what you needed. However, you could see they treated the black press better. I was never going to be a ‘brother,’ no matter what I did or how hard I worked.”

RUMOURS OF A MUTINY

One difficult moment occurred when Motown’s top goldminers fell out with Berry Gordy. Hints of the discord had been regularly reported in Billboard by Ochs: “There seems to be trouble brewing in Motown country with rumors of a Holland/Dozier/Holland mutiny,” he noted in Soul Sauce in one issue. “Still no word – or music – from Motown’s Holland/Dozier/Holland team, though Motown is two million singles ahead of last year, with five hot discs working now,” Ochs reported in another.

When the trio’s departure was finally confirmed, “Motown called Lee Zhito and asked him to hold the story, so I know they didn’t want it in print. Lee told them it was news and we had an obligation to run it, that word was already out on the street and we’d be scooped, and so on. And it ran, without any recriminations toward Billboard or myself.” (Run it did, but hardly with prominence: a lesser story, for instance, about White Whale Records acquiring a Jerry-O master played bigger, with its own headline.)

‘Don’t let ‘em run that story’

There were other tensions because of the colour of the magazine’s R&B editor. “Jerry Butler had an attorney send Billboard a lengthy notice demanding that I never mention his name in Soul Sauce,” said Ochs. “I assumed he found out I was white.” Then again, it’s possible that it had nothing to do with race. “It was hardly uncommon in those days for artists and record companies to be angry about chart positions, and they’d let us know it!”

As the 1960s gave way to the ’70s, Billboard gained strength as the record industry’s leading trade paper, while black music grew in both creative stature and commercial clout. In 1969, Ochs had suggested changing the charts’ name from R&B to Soul, and that nomenclature continued for 13 years. In 1971, he was given an award by NATRA for his contributions to black music – a different kind of recognition to that he received during its 1968 gathering.

“I enjoyed a lot of support in the industry,” Ochs concluded, “from record company presidents to artists to newspaper columnists and fans communicating with Soul Sauce.” Interviews with Lou Rawls, James Cleveland, Elvin Jones, Nina Simone, Melvin Van Peebles and Aretha Franklin stand out in his memory, while personal favourites among Motown artists included Martha Reeves and Stevie Wonder. He also wrote liner notes for albums by Tammi Terrell, Jr. Walker & the All Stars, and Smokey Robinson & the Miracles.

“If some of the more militant blacks gave me a hard time, well, maybe it was because I was in the wrong place at the wrong time. That I understand. Jean Williams and, later, Nelson George continued with Soul Sauce after I left in 1971, so perhaps the right people got the right job after all.”

MJ notes: Ed Ochs rejoined Billboard in 1981 on its special issues team, and experienced another reunion. He had interviewed Michael Jackson in 1971 (“I met his parents, checked out his rehearsal room, and played one-on-one basketball with him”) and, 13 years later, he worked on the production of the magazine’s Thriller special issue. “Michael had to approve the layouts, or there would be no special,” Ochs recalled. “He returned the next day for another look, and we talked about the art, how I used the photos, married the editorial, art and photos, and put together each page. He was normal, open, friendly and alert as I’d never seen him in public or in behind-the-scenes footage. He called the next day to thank me for the ‘guided tour.’”