A Longer ‘Life,’ After All

STEVIE’S ‘EXPERIMENTAL’ SOUNDTRACK RECONSIDERED

The photographer asked Stevie Wonder to sit at the piano.

It was next to a large potted plant, in Motown Records’ HQ on Sunset. Obligingly, he did so, then pretended to bite one of its leaves. “Hey, that’d be a good caption,” he declared to his Los Angeles Times interviewer. “ ‘Stevie Wonder doesn’t only sing about plants, he eats them.’ ” He added, “If Plants doesn’t sell as well as Motown expects, I might also have to eat the album.”

The figurative meal would have been filling. Motown shipped 1.2 million units of Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants for its U.S. release on October 30, 1979. According to president Jay Lasker, the company eventually took back 550,000 copies, unsold.

Stevie, unlimited

That Wonder’s idiosyncratic soundtrack closed out his most accomplished, inspiring decade as a disappointment is the accepted wisdom. And yet 25 years after the double-album’s release, the musician singled it out as one of his quintessential works. “I just think that if you have a love for music,” he told Billboard’s Gail Mitchell, “you cannot limit yourself to any particular kind of music.”

It was, he added, “an experimental project with me scoring and doing other things I like: challenging myself with all the things that entered my mind from the Venus’ flytrap to Earth’s creation to coming back as a flower.”

A younger generation appears to agree: those who grew up able to order à la carte from Wonder’s entire music menu, chosen from a distance rather than at the moment of release. Now that’s a feast.

The names of those influenced by Life of Plants can surprise, from Solange Knowles to Prefab Sprout’s Paddy McAloon. “I think through the evolution of music that really enriched me during this time – whether it be Stevie Wonder’s Secret Life of Plants or it be Steve Reich or it be Alice Coltrane – these are artists who have used repetition in those projects to really reinforce their frequencies,” Knowles told The Atlantic a couple of years ago. “I can remember feeling liberated enough to stretch myself lyrically,” recalled McAloon to Mojo in 2004. “On ‘Outside My Window,’ you can hear echoes of ‘Isn’t She Lovely,’ but he’s singing to petunias rather than a baby. In fact, if you actually read most of the lyrics, they’re a bit daffy – but, of course, it’s Stevie Wonder singing them, and when a voice has such musicality to it, it’s way more than the sum of its parts.”

India.Arie was sufficiently inspired that she named her second album, Voyage to India, after a track on the Wonder work. The Roots’ Amir “Questlove” Thompson told Pitchfork that the music “marked a special awakening moment for me because I was used to Stevie’s pop magic, so I was a little weirded out that these weren’t songs. I often wondered, ‘Why would you take such a risk?’ Now, I live that question.” At the New York University course about Wonder taught by Motown catalogue maestro Harry Weinger, Questlove said, “I used to just sit and imagine [the film], even without any video.” The album was also his first headphone experience, at the age of eight.

AN INTUITIVE, FEARLESS EXPLORATION

Pitchfork has published perhaps the most thorough musical assessment of Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants. The singer/songwriter “literally branched out…exploring intuitively and fearlessly in a manner that few artists have ever managed to do in the history of pop music,” asserted writer Andy Beta in 2019. But there are countless backroom stories about Wonder’s involvement with the film and its soundtrack, and Motown’s experience with the result – tales of pioneering sound and perfume, of perpetual delays and top-hatted concerts, and, of course, of plants.

The movie was based on the best-selling 1973 book by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, an account of “the physical, emotional, and spiritual relations between plants and man.” It was announced in the Hollywood trade press the following spring (“Now filming around the planet”) with producer Michael Braun and director Walon Green. Braun is said to have approached Wonder in 1975 about creating the soundtrack, and there’s evidence that the Motown superstar was working on tracks like “A Seed’s A Star” in the autumn of ’77 at Philadelphia’s Sigma Sound studios.

Stevie, in full bloom

According to onetime Sigma staffer Arthur Stoppe, Wonder was so aware of his surroundings that when he handed a cassette to an engineer for playback, he was able to identify the model number of the tape machine by the sound the door made when it dropped open. “I see you have a Nakamichi 700,” he said, by Stoppe’s account. Later, Wonder bought his own cutting-edge technology, a Sony PCM-1600 digital recorder, for use in creating the soundtrack – which turned out to be one of the record industry’s first digitally-made albums.

Meanwhile, filmmakers Braun and Green were confronting cinematic problems, including lack of enthusiasm at distributor Paramount Pictures for the picture. It was due for release in 1978, but became delayed – and Wonder began reworking instrumental tracks into vocals, among other tweaks. Motown played extracts of the soundtrack to its international licensees in Cannes in January ’79, with the record’s release set for February or March. This being a Wonder project, though, the clock kept ticking.

“To herald [the album’s] arrival, I was going to send you the enclosed packet of sunflower seeds,” noted David Hughes, Motown’s general manager at EMI Records in London, writing to U.K. retailers. “However, as now is the planting season, I send you the seeds anyway. Plant them, watch them grow, and be assured that Stevie Wonder’s new album is coming – at least by the time these flowers are in full bloom.” He concluded, “Thank you for your patience.”

The months went by, accompanied by fraught internal discussions at Motown. Barney Ales was leaving as president, but Berry Gordy still sought his advice as a consultant. He met with Wonder’s principal advisors, Johanan Vigoda and Ewart Abner. “I said it’s not going to sell as a double album,” recalled Ales. “There’s only one good song in there. Cut it down to one album.” It was not a popular idea, nor heeded. “They were banking everything on the motion picture. And that was horrible.”

NATURAL SOUNDS, PRODUCT ENDORSEMENT

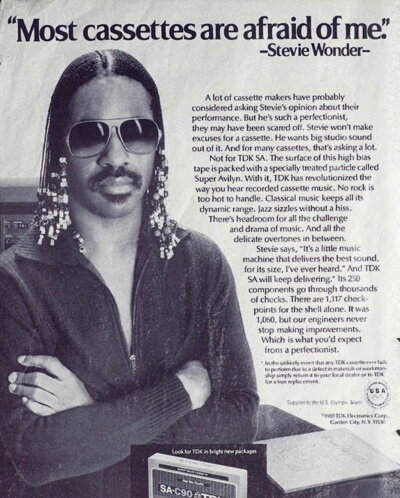

Finally, an October release date was firmed up. As it became obvious that the film wouldn’t provide the desired sales stimulus, other plans took shape. Wonder’s profile had risen in the summer through his endorsement of TDK blank tape – controversial, as the record business was of the view that home taping hurt sales – and he was featured in print and TV advertising for the brand. “Natural sounds go into my music,” declared the musician in one 30-second spot, with Life of Plants music playing.

The album’s packaging was another challenge. The three-panel foldout was more than the traditional 2LP enclosure and costly to produce, with a specially embossed front cover and a Braille inscription. Wonder’s image did not appear on the front or back of the packaging. Early pressings also featured a Gardenia scent embedded into the sleeve wraparound. In the U.K., however, Motown’s licensee discovered that the scent “melted” the vinyl, so the idea was abandoned abroad.

Stevie, on the merits of TDK

To Motown’s relief, Wonder embarked upon a substantial publicity campaign for the set, including launch events in Malibu and New York. The latter took place at the city’s botanical gardens in the Bronx, with busloads of media brought in – although the conservatory acoustics weren’t ideal for audio playback. Nevertheless, the star was on message, and an Associated Press interview gained particular traction around the world. “I used a machine designed for me,” he explained to AP writer Mary Campbell. “I can record the sound of a bird, go into the studio and put 10 seconds of it into the computer, where it is stored. I connect the synthesiser and keyboard up to the computer, which enables me to play whatever notes I want of the bird singing.”

Of the prospect that Life of Plants might not be what the public was expecting of him, Wonder told Campbell, “No one should deny an artist a chance to express what his experiences are. If it’s not true, then I would not desire to be an artist. If I cannot grow and be expressive of my inner self, there is no need for me to be in the world of music.”

A crucial part of that world – the charts – welcomed Wonder in November, first with a single, “Send One Your Love,” then the double-album. Both reached the Top 5 in Billboard, buttressed by a six-city tour in December, including a show at New York’s posh Metropolitan Opera House. “Rare and courageous,” opined your correspondent for the trade mag, “is the recording artist who performs virtually the entire contents of a brand new album only a matter of weeks after its release. It certainly asks much of an audience.”

Yet Wonder’s instincts weren’t entirely devoid of commerce. After the National Afro-American Orchestra – complete with brass section in top hats and tails – brought another dimension to his Life of Plants performance during the first half, he opened the second with a time-machine cameo of his 1963 self, introduced as Little Stevie Wonder, performing a full-length version of “Fingertips – Pt. 2,” his very first hit. “Complete with period dark glasses and ill-fitting jacket,” I wrote for Billboard, “this was a good-humoured acknowledgement of his Motown past, displaying a grace seldom matched by others from the era.”

As Jay Lasker later made plain, the financial outcome of Stevie Wonder’s Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants wasn’t as dollar-green as the company’s hopes. But the creative – and spiritual – impact evidently outlived those days. “It seems a little unfair that this was so badly received when it came out,” said Prefab Sprout’s McAloon. “Some of the little chants in there could almost be Sun Ra or something. Whenever I see this album in a charity shop, I can’t not buy it. I’ve got three or four copies of it at the moment. I’m continually handling them out to people.”

The journey continues.