For Love or Money?

WHEN MARVIN WAS REMEMBERED (AND WHOSE SONG WAS IT?)

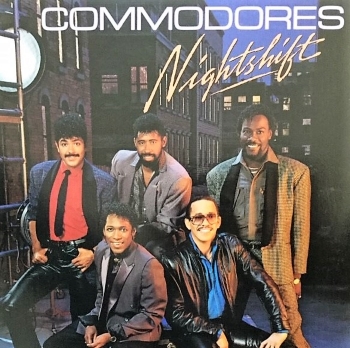

To this day, Martha Reeves doesn’t mince her words. Nor did she in the spring of 1985, when two tributes to the late Marvin Gaye ruled the summit of the Billboard R&B charts, back to back: “Missing You” by Diana Ross and “Nightshift” by the Commodores.

“I’m just sorry people are capitalising on his death,” said Martha in a newspaper interview, “taking all that love and devotion and turning it into money.”

Then again, both “Missing You” and “Nightshift” captured the sense of loss widely felt about Gaye’s death the previous year. The principals involved with Diana’s tribute certainly knew Motown’s prince. “It actually came out of a conversation that Smokey Robinson and I had one evening about how we were missing Marvin,” Ross later explained, “and what he meant to us, as well as to music. Then Lionel and I got to talking about how we need to tell people that we love them while they’re still alive. Lionel used all this to write that beautiful and special song.”

The roots of “Nightshift” are rather more contentious, but let’s stay with “Missing You” for a moment. That, of course, wasn’t the first union of Richie and Ross: their “Endless Love” in 1981 was the biggest single in Motown history to that point, with three million in sales. Moreover, Lionel had gained insights into Diana’s work through observing Berry Gordy, who let him into the studio while he oversaw 1973’s Diana & Marvin album.

Ross recorded “Missing You” in New York in mid-1984 (just months after Gaye’s death on April 1) for her fourth post-Motown album, Swept Away, released by RCA Records that September. Richie played keyboards on the session, arranging and producing the song with James Anthony Carmichael, his longtime Commodores collaborator. It sparked into life as a single in November; the promotional video clip maintained Ross’ links with her past by not only including footage of Gaye, but also evocative images of other fallen Motown stars, including Florence Ballard and Paul Williams.

In addition to topping the R&B charts in March of ’85, “Missing You” reached the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 in April – the last time Diana did so. She included the song in the setlist of her North American concert tour that year, and performed it with Smokey in August for an episode of his network TV series, The Motown Revue Starring Smokey Robinson.

“Nightshift” proved to be an even more popular tribute to Marvin, which helped the Commodores to regain – for a moment – the chart stature they had enjoyed when Richie was their lead singer. The record was a Top 3 success on both sides of the Atlantic, and grabbed a Grammy for R&B Vocal Performance, the band’s first such statuette. (“Missing You” garnered no nominations.)

THE COMMODORES REGROUP

Two years before Marvin’s father killed his son, the Commodores had experienced a loss of their own, when manager Benny Ashburn, the wizard who transported them, in Lionel Richie’s words, “from the ground floor to the top of the world,” died unexpectedly. Around the same time, Richie quit the group, and producer Carmichael went with him. In 1984, guitarist and founder member Thomas McClary also left.

To recover and regroup, the Commodores reached out, first to singer J.D. Nicholas, then to producer Dennis Lambert. Nicholas joined after working as a session singer (behind Diana Ross, among others) and, before that, as a member of Heatwave, the British soul combo. Lambert, meanwhile, had begun to move in Motown circles through his acquaintance with Jay Lasker, the record company’s president in the ’80s.

For The Billboard Book Of Number One Rhythm & Blues Hits, the co-author of “Nightshift,” Franne Golde, told me, “The band had approached Dennis to work with them. Of course, Lionel had left and they really hadn’t had any success. Each member wanted to [continue to] write, so they each submitted ideas. One of them, by Walter Orange, was this little groove he had going, which was the bass line to ‘Nightshift.’

“Dennis played me a few things, and then he played me that. The only thing in the song was, ‘Marvin, he was a friend of mine.’ That was all he had. I said, ‘This is fabulous, I love it.’ When Dennis said, ‘We need to make this like ‘Rock and Roll Heaven,’ I said, ‘Great, let’s do it.’”

“Rock and Roll Heaven” was the 1974 pop drama by the Righteous Brothers, which Lambert co-produced, about rock’s departed: Otis Redding, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and more. Lambert suggested the idea of an update soon after Golde happened to see the 1982 Henry Winkler/Michael Keaton movie Night Shift on TV.

In her mind’s eye, Golde – who is today a clothes designer – pictured singers on the nightshift in heaven, “coming out and giving their concert. And right when I explained that, Dennis said, ‘Gonna be some sweet sounds comin’ down on the nightshift.’”

The song “wrote itself” from then on, according to Golde. “It took two mornings in the studio, while Dennis was in with the Commodores. We got The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits and looked up Marvin Gaye and Jackie Wilson. I wrote down all the titles of their songs, and we incorporated them into the lyric.”

SHIFTING THE CREDIT

Lambert cut the Commodores in Los Angeles, augmenting the group’s instrumental skills with such session professionals as Peter Wolf on keyboards and Paul Jackson on guitar. Wolf also did the arrangement. Singing lead on “Nightshift” was the song’s originator, Walter Orange, who had vocally co-fronted the group in their early days. Said Golde, “Originally, Walter had sung the whole song. But then it was so great when Dennis decided to put J.D. in the second verse. It just worked so wonderfully.”

The originator? In Thomas McClary’s 2017 autobiography Rock & Soul (written with Ardre Orie), the musician singled out one of the band’s meetings with Lambert, when he played some of his new songs, “one of which revealed an innovative sound with an arrangement that was quite different. There was a sustaining bass sound that caught everyone’s attention.”

Lambert reacted positively, by this account, saying, “ ‘Wow, that is amazing. Are you going to submit that song for the record?’ The next thing I knew, he invited us back to listen to a song called ‘Nightshift.’ As I listened, it was more than familiar. It was the concept that I had played for them.” In his book, there was no doubt: “Walter Orange and Dennis Lambert had stolen my musical concept and arrangement.” By the time “Nightshift” was a hit, McClary was out of there.

Sour relationships among previously close friends and colleagues are as common in music as elsewhere. The media continues to be interested, for example, in what are said to be frosty feelings between Diana Ross and Mary Wilson. Once upon a time, David Ritz, co-writer of “Sexual Healing” and author of Gaye’s well-regarded biography Divided Soul, sued the singer over the lack of composing credit for that song. Just 15 months ago, Thomas McClary’s former bandmates won a legal action to restrict his commercial use of the Commodores’ name.

If rock ’n’ roll heaven is populated by singers and musicians, some of them probably wish they could call their lawyers on the nightshift. Maybe Martha Reeves was right: there’s love, devotion – and then money.

Music notes: in addition to “Missing You” and “Nightshift,” there have been other tributes, including Stevie Wonder’s pensive “Lighting Up The Candles,” which he sang at Gaye’s funeral and later recorded for his Jungle Fever album; Frankie Beverly & Maze’s glossy, undulating “Silky Soul”; and Teena Marie’s adoring “My Dear Mr. Gaye,” one of her best. All are on digital music services, unlike Edwin Starr’s melancholy “Marvin,” released as a single in 1984. More recently, singers have started to use the Marvin’s music and memory as a lyric line, most obviously in 2015’s “Marvin Gaye” by Charlie Puth with Meghan Trainor. Then there are the samples…