London Calling

MOTOWN’S UP AND DOWNS IN PURSUIT OF BRITISH TALENT

Third time lucky?

A few weeks ago, Motown Records announced that it had opened a new subsidiary in London, “to sign and develop exciting new British talent, expand our platform for black entrepreneurship in the U.K. and guide Motown towards even greater global success.”

The words were those of company president Ethiopia Habtemariam, declaring her ambitions, much as another executive had done three decades earlier. “This new operation will be the linchpin of Motown’s continuing growth,” said Harry Anger, who was its COO on that occasion: February 18, 1993, to be precise. “It will also provide this company with a launch vehicle for our new artists in the United Kingdom and serve as a gateway to Europe and the rest of the world.”

Twenty years before that, the mission statement was rather more modest. “We’ve been given a budget from the States,” revealed John Marshall, Motown Records’ deputy international director, to Billboard in March 1973, “but we will be an autonomous operation in the U.K.” He added, “We have a free hand to develop British talent.”

New generation: Kreuz with Nicki Denaro and Rahim Jung

Today, the responsibility for Motown U.K. lies with newly-appointed managing director Rob Pascoe, as it did in ’93 with the unit’s general manager, Nicki Denaro, and in ’73 with John Marshall. As it was for his predecessors, Pascoe’s challenge will be to find, sign and develop local talent with commercial appeal in Britain and beyond. Assuming he has some success with that, Pascoe will be hoping for long-term support from Motown in the United States, which apparently was not the case in 1993.

What happened with that adventure? “Absolutely fuck all,” Denaro told me recently. She was recruited to run the London-based unit because of her years of marketing Motown at RCA Records, when it was the American firm’s international licensee. In 1992, Motown president Jheryl Busby and A&R chief Steve McKeever were introduced to the principals of a promising U.K. production outfit known as ARP. “They had this act called Kreuz,” recalled Denaro. “They were a really good band, and ARP had this feel as a really good indie production company. The music was great. Plus, it was just getting to the stage where [BBC] Radio 1 wouldn’t throw you out the door if you had a record by a black artist and they already had one or two of those on the playlist.”

Motown publicised the new setup with Kreuz as its first signing, touting the trio “as one of the most promising young R&B groups to emerge from the U.K. in years.” The band’s first single in March 1993 was “When You Smile,” followed by their album, New Generation, a few weeks later. Marketing and promotion duties for Motown in the U.K. were then primarily in the hands of PolyGram, which had succeeded RCA as Motown’s international partner. But PolyGram wasn’t interested in the British initiative, according to Denaro. “It was a typical example of company politics getting in the way of an act actually having a shot at breaking through.” The Kreuz album did not trouble the U.K. charts, nor was it released across the Atlantic.

STAND-ALONE LABEL

Denaro’s assessment is shared by Mervyn Lyn, who worked on Motown at RCA and PolyGram, and introduced the ARP team to Jheryl Busby, Harry Anger and Steve McKeever. “ARP was very tuned in,” he said, “and Kreuz were good.” According to this account, Motown wanted a stand-alone U.K. label, having previously signed Kiss The Sky, a British act featuring Paul Hardcastle and Jaki Graham, directly to Motown U.S., and also cut a deal with Jazzie B’s Funki Dred Records. In the event, neither made an impact. “Steve could be quite eclectic in taste,” added Lyn.

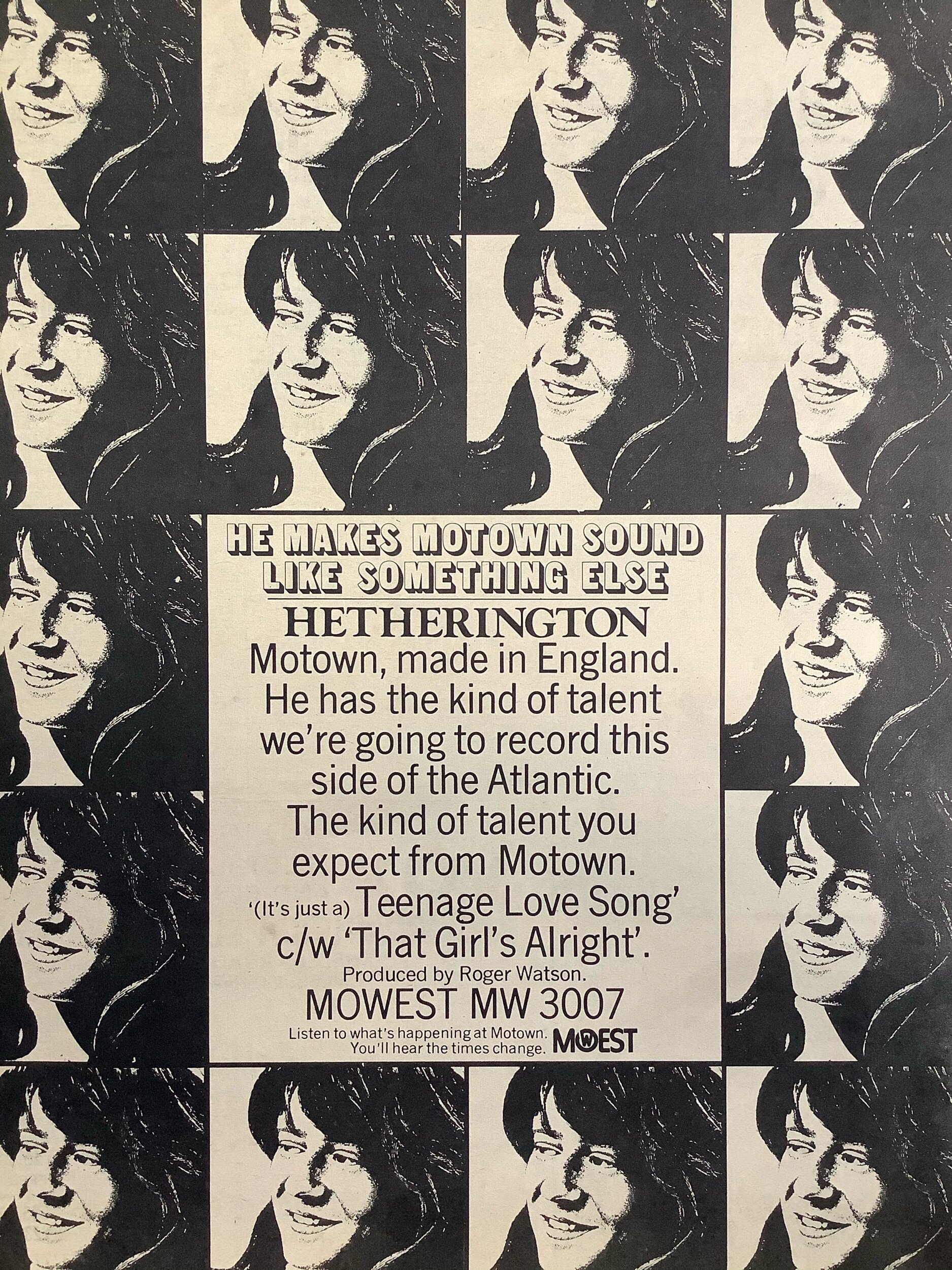

The kind of talent you expect…

No other acts were signed to Motown U.K. in 1993, but that was not for the lack of material. “We got inundated with all the crap from every nutter in existence,” said Denaro. She had a young promotion staffer, Rahim Jung, with good ears “who was going out around the clubs, finding stuff,” but despite submissions to McKeever in Los Angeles, there was no further interest from Motown there. “It was a bad experience for Rahim. He was a good lad – and he converted to Islam soon after!”

This British unit was shut down shortly after PolyGram bought Motown Records in its entirety in August 1993, and Denaro departed. “I wasn’t surprised,” said Mervyn Lyn, “as I always felt PolyGram’s focus was on catalogue reissues and not front line.” He certainly was in a position to know, serving then as general manager of Motown within PolyGram International. For her part, Denaro today prefers to remember other moments of her Motown years, such as Stevie Wonder singing “Happy Birthday” to her from the stage of a London concert hall.

Two decades earlier, Motown’s U.K. talent venture under John Marshall and his A&R lieutenant, Trevor Churchill, yielded a variety of singles by mostly pop artists. Only one saw significant chart and sales action – in Germany, rather than in Britain – but it helped to make the operation profitable. Just a handful of these recordings were released in the U.S.

“I was the main, and probably the only, one pushing for Motown to look at the U.K. as a source of product,” Marshall told me. “I can’t recall anyone else in the U.S. showing any real interest.” He had been a Motown label manager at EMI Records when the latter was the American company’s overseas partner, then in 1969 was hired to establish its own, separate London presence. The formation of the U.K. production company followed in 1973, with singles issued locally on the MoWest (10) and Rare Earth (9) imprints over the next two years.

“We were just taking a small punt to see if we could get a hit in Europe,” continued Marshall, “which, if successful, could translate to success in the U.S. and give us more freedom to source more U.K. product.” Although the Americans had no creative input, all the artist contracts were with Motown U.S., and Marshall reported to Detroit-based vice president Ralph Seltzer.

The modest scale of the British venture was also shaped by the spiralling costs of rock talent. Churchill explained, “1973 was a time when managers were able to ask for astronomical advances and royalties because there was so much demand for the latest rock act.” Motown U.S. would have questioned the risks of such deals, especially when compared to the consistent, substantial royalty income coming from its American repertoire sold through EMI.

PLAYING AND SINGING EVERYTHING

That July, singer/songwriter John Hetherington’s “(It’s Just A) Teenage Love Song” was the first 45 from the British branch, out on MoWest. Next up was Phil Cordell, a multi-talented musician who had previously enjoyed a Top 5 hit, “I Will Return,” as Springwater. “Phil had a home studio down in Sussex where he played and sang everything,” said Churchill, “and turned out many pop ditties under many pseudonyms.” Cordell’s first MoWest single was “Close To You,” also issued that summer.

Motown U.K. 2020: Rob Pascoe and Afryea Henry-Fontaine

“That didn’t do anything,” Churchill went on, “but [Cordell] had this really catchy instrumental called ‘Dan The Banjo Man’ which we released on Rare Earth in August 1973. We were keeping what we considered the classier stuff on MoWest.” The record was a bust in Britain, but barrelled to Number One in Germany the following spring, buttressed by the tune’s use in a TV commercial for orange juice.

Churchill had accumulated many industry contacts over the years, not least from his time running the Rolling Stones’ record label. He brought American producer Peter Anders to London to work on a variety of projects, including MoWest/Rare Earth releases by the Rockits, Sonny & the Sovereigns, Rough Riders and Friendly Persuasion – some of which featured Anders himself, performing with associates Kenny Laguna and Paul Naumann. For this, Churchill set up a small studio and rehearsal room in London.

Phil Cordell, meanwhile, tried to follow “Dan The Banjo Man,” but in vain. He also lost out to Neil Sedaka in a cover-version battle with “Laughter In The Rain,” and attempted another instrumental, “I Can’t Let Maggie Go,” under the name Riverhead. Still, he was re-signed to Motown’s Prodigal label in 1977, with an album, Born Again.

As Nicki Denaro experienced with the second edition of Motown U.K., the first initiative was largely dependent on the promotion and marketing facilities of another company – in that case, EMI. Whether it was the result of repertoire or resources, the British A&R adventure came to an end six months after Churchill’s departure in December 1974. For his part, John Marshall continued to direct Motown’s international operations from London, with primary emphasis on American artists.

In 2020, Rob Pascoe and his marketing director, Afryea Henry-Fontaine, may have more advantages than their forerunners. The timing “could not be more perfect” for the initiative, according to Ethiopia Habtemariam. Given that Motown today is part of the world’s largest music company, Universal Music Group – occasionally called the “Death Star” by industry jokesters – she could be right.

Third time lucky?

West Grand Blog is taking a short autumn break. See you back on the boulevard soon, with luck.

Music notes: Motown acquired and released music by British artists several years before setting up a U.K. production company in 1973, but these were recordings already made for other labels, picked up for the American launch of Rare Earth Records in 1969. Among them: albums by Love Sculpture, Toe Fat, Sounds Nice and the Pretty Things, all licensed from Britain’s EMI Records. In later years, Motown did U.S. distribution deals for the likes of U.K. labels such as Gull and Manticore.

Rabbit hole notes: a listing of the singles recorded and released on the MoWest and Rare Earth labels in the U.K. from 1973-75 (most of which were never made available in the U.S.) can be found on the rather engaging Seventies Sevens website. These are tabulated with the American 45s also issued on those labels. Here, you can check out MoWest and Rare Earth.