A Time of Fire

MAGNIFICENT MONTAGUE SPINS AND BURNS

“Once you heard his outrageous oratory,” declared Berry Gordy, “you couldn’t forget it or him.”

Smokey Robinson knew the orator, too: “He was splendid in his ability to captivate the listening audience, superb in his role as a community leader, and noble in the way he showed young people how to move through life with class.”

Gordy’s second wife, forthright as usual, raised another matter. The disc jockey “uncovered numerous scams involving millions of company dollars,” wrote Raynoma in Me, Berry, and Motown, “and, due in part to his findings, certain well-salaried heads rolled.”

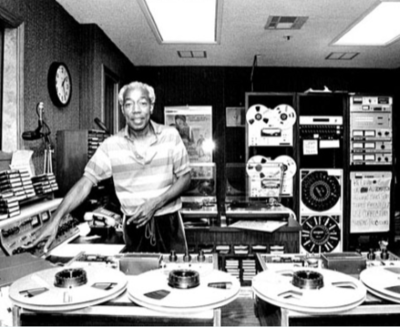

Magnificent Montague in the studio, circa 1984

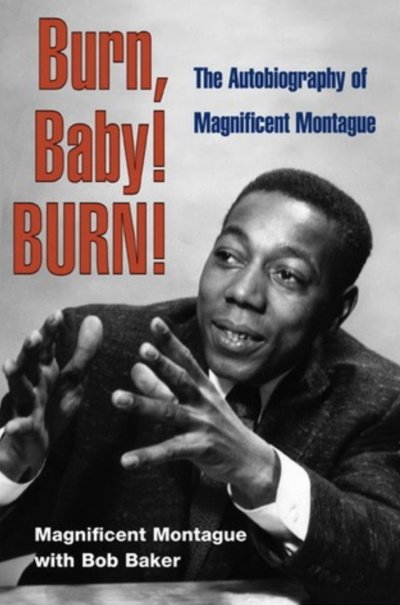

But first and foremost, Magnificent Montague – for it is he – spun music, magic and poetry on a score or more of R&B radio stations across the United States during the 1950s and ’60s. “Black heaven was where I tried to take my listeners through rhyme and verse,” he wrote in his autobiography with Bob Baker, Burn, Baby! BURN!

In that goal, Montague succeeded, while also maintaining an allegiance to black-owned record companies such as VeeJay, Motown and Duke/Peacock, touting their output and spreading their wares as he segued from one station to another, from San Francisco’s KSAN to New York’s WWRL, from Chicago’s WVON to Los Angeles’ KGFJ.

Motown’s founder was certainly appreciative. “I always get a good feeling when I think back to how they, the jocks in black radio, many of whom I never met, took so much pride in helping me, a young black cat out of Detroit,” Gordy noted in To Be Loved.

Still, it’s Montague’s spell at KGFJ for which he’s most remembered – and not always positively. “Burn, baby! Burn!” was one of his several signature slogans, sent into the airwaves to capture the spirit and excitement of the records he played, and to raise his audience’s temperature. As a result, listeners across the nation came to know the catchphrase.

WHOSE SLOGAN WAS IT?

The trouble started when the Los Angeles district of Watts went up in flames in August 1965. As streets, buildings and automobiles blistered and burned, Montague kept using the triplet. “It was my slogan, not the rioters’,” he asserted, and he was all about the music. But as the riots intensified, the DJ was accused of incitement, not least by the mayor of Los Angeles. Eventually, Montague stopped, switching to “Have mercy” as his on-air identification in the City of Angels.

But before that change, San Francisco record retailer and label owner Ray Dobard threw petrol onto the blaze. A late-August ’65 edition of his Your Choice of Hits weekly newsletter, mailed to some 300 DJs nationwide, called upon “All Soul Brother DJ’s around the United States [to] use Magnificent Montague’s tactic and help to BURN DOWN some of those other ghetto towns that should be burnt down. BURN BABY, BURN ! ! !”

Montague interviews singer/bandleader Cab Calloway in Chicago, circa 1955

Predictably, this provoked an investigation by California authorities, and brought Dobard perilously close to prosecution. In response, he claimed that his words had been misinterpreted by “backbiters and nonsoulful square competitors and Ray Dobard haters that exhibit ignorance of the Negro jargon, Negro language and Negro culture.”

That aside, Dobard was merely one of Magnificent Montague’s many friends, acquaintances and allies in the music business, such as Specialty’s Art Rupe, King’s Syd Nathan, Duke’s Don Robey, Phil and Leonard Chess – and, of course, Berry Gordy. On one occasion in 1960, the Motown monarch asked the disc jockey to address his Detroit team, to help them understand the business of music as much as its creation.

“I tried to do it like a show,” Montague recalled in Burn, Baby! BURN! “I talked historically, about black participation in American popular music, the famous songs that nobody ever had a clue blacks wrote.” He also spoke about the fate of the black-owned Black Swan label (“decades before anybody thought of Motown”) at the hands of white-owned major labels and distributors. “When you have whites heading up your main sources of distribution and collecting the money, you must be careful, because most of them are thieves. They bear watching.

‘LET THE BLACKS GET A PIECE’

“You know the distribution agreements, you know the deals on the records, you know how to get the money under the table – and the best way to safeguard this is, I suggest, to have your white business people on top and put the blacks right there by their sides, and if there’s going to be any thieving or stealing, let the blacks get a piece.”

Montague’s own skill at getting a piece was codified in Burn, Baby! BURN! After being fired from WVON Chicago in 1964, he relocated westward – with help. “I sent him money for his cross-country move to Los Angeles,” admitted Berry Gordy. “Sometime later, I was shocked to find that other manufacturers had paid for that same move.” Montague’s response to BG? “My dear man, you wouldn’t expect me to deprive anyone of the pleasure of helping the Magnificent One, would you?” In fact, he confessed, “a few other record companies also took care of my moving charges to L.A. I made a profit before I even got there.”

The autobiography, published in 2003

Not that this diminished his stature. In 1976, Gordy even assisted in the funding of a Los Angeles gallery showcase for the DJ’s extraordinary collection of black cultural artefacts, including books, paintings, posters, coins, cards, letters and more. (Among the first gallery visitors: Diana Ross.) Shortly after that, Montague was hired at Motown Records as special assistant to president Barney Ales.

It was a curious appointment, presumably commissioned by Gordy to make the most of the broadcaster’s contacts, insights and experience. “As far as [Montague] was concerned,” Ales once told me, “I was an ofay. He definitely disliked white people, he tolerated me because of my position, and what I could get done. We had a mutual understanding that we disliked each other – but he was very bright, thinking ahead on black situations.” Another of Montague’s ofay acquaintances was the late Claude Hall, Billboard’s radio editor. “He was a good and close friend,” said Hall, who was typical of the industry influencers that the disc jockey knew so well.

And Miss Ray’s experience? She claimed in her memoir that during the period when Montague was on the Motown payroll, he discovered dodgy dealings within. One of the worst transgressors, she wrote, was “a top white cohort of Berry’s,” who subsequently went to prison – well, a work-release programme – for tax evasion. Montague, however, became disillusioned after that executive was subsequently rehired by Motown.

And so this pilot of the airwaves returned to radio, as a station owner and operator in Palm Springs, California. His KPLM-FM became a popular easy-listening outlet in the early ’80s, spinning the likes of Glenn Miller and Count Basie, Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, the Andrews Sisters and the Ink Spots.

Yet it was impossible to forget the true, soulful legacy of Magnificent Montague – and he knew that. “For my time on the radio was indeed a time of fire,” he wrote in a 1994 article for The Los Angeles Times. “It was a time when music and society and race and technology all exploded like a bomb, a time when black DJs made R&B erupt out of that old marketing niche of ‘race music’ and changed the way young Americans – white as well as black – saw their world. To live in that vortex was to touch America’s soul and be touched by it.”

That sounds like a pretty good definition of Motown’s impact, too.

Broadcast notes: reading about Montague is, naturally, a lesser experience than listening to him. Among the best ways to sample that distinctiveness can be found on his website, including this, his own theme tune (you might recognise a voice from Detroit in back), and an exciting introduction here to one of the finest soul stars of the ’60s. Also, there’s an insightful National Public Radio interview with the DJ and his autobiography’s co-author, Bob Baker, from 2003 via this link (with luck). Have mercy, baby!