Words Worn on Their Sleeves

NOTES TO ACCOMPANY ‘YOUR LISTENING PLEASURE’

From showbiz superstars to storied songwriters, from television titans to trade-press editors, from radio rulers to company insiders. All these and more have put words on paper to hail the music of Motown and those who made it.

Among them: Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis Jr., Dinah Shore, Ed Sullivan, Jule Styne, Gene Kelly, Carol Channing and Elton John.

Some of Motown’s own stars even did this themselves (or appeared to) once in a while, including Smokey Robinson, Mary Wells, Diana Ross, the Temptations, Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder.

Welcome, then, to the world of album liner notes and those who wrote them, for love or money, or both. They were customary when Motown first began releasing long-playing records. Of course, the prose was primarily window dressing; it was the music which motivated a purchase. Moreover, the company’s target audience at the time mostly bought singles. What was Berry Gordy’s famous question during those early Quality Control meetings? “If you were hungry and had only one dollar, would you buy this record or a hot dog?”

The work of Billie Jean Brown

Who on earth could afford an LP?

That said, Motown added liners (or sleeve notes, to use another description) to many of its albums during the first half of the ’60s. Most were written inside the firm, or by record industry peers – disc jockeys, for instance – who knew the music. Until Gordy’s performers became household names, the practice of asking an outside star to endorse an LP was rare. The first example? That seems to have been the praise heaped upon Diana, Mary and Flo by Sammy Davis Jr. for The Supremes at the Copa, towards the end of 1965.

In 1961, Hi We’re The Miracles was Motown’s first long-player, and, as the title suggests, the group introduced themselves with words as well as music: “In this album, you will find some of our best hits and originals, which we hope will add tremendously to your listening pleasure.” There followed a brief description of their origins, and then a couple of paragraphs – written in the third person – about each individual member. The notes concluded: “They want to take this opportunity to extend their deep appreciation to all of their marvellous fans for making this album possible.”

This was probably the work of Billie Jean Brown, the youngster hired part-time at Motown in 1960 to write press releases and serve as a general assistant. She had edited the school paper at Detroit’s Cass Tech, and was highly knowledgeable about music, too. She joined the firm full-time the following year, ostensibly as a receptionist, but she soon took on the task of tape librarian; her celebrated role overseeing Quality Control followed in 1963. During this time, Brown was credited as the author of at least a dozen sleeve notes on Motown albums, including three by Little Stevie Wonder, a couple by Mary Wells, and the Supremes’ debut. “So…with diplomas on their walls, we present, along with their smash single, “Your Heart Belongs To Me,” a medley of tunes enabling you to “MEET THE SUPREMES,” she wrote.

Brown’s style was efficient and crisp. “One of the greatest tributes that can be paid an artist is for another to admire him enough to record his material,” declared the intro of her notes for Stevie Wonder’s Tribute To Uncle Ray. She could also do hyperbole: “Another fantastically great album from the fabulous Miracles!” opened the liners of Recorded Live: The Miracles On Stage. And she could be economic: “A dimming of the lights, a flash of red and the vivacious Mary Wells is on stage performing for you.” Those are fully half of the 39 words which concisely graced the back of Recorded Live: Mary Wells On Stage.

Ed Ochs calls for Junior’s home cookin’

There was the odd mystery. The liners for the various-artists album Recorded Live at the Apollo Vol. 1 were clear, colourful and well-punctuated (“The artists’ performances are actual…the audience reaction is real…the spontaneous brilliance stands out.”). The notes were credited to Q.C.A. – Quality Control Assistant? Quality Control Administrator? – but so was the cover design, and Brown wasn’t a designer.

But mystery better befits the single most prolific writer of credited liners at Motown, Scott St. James. This name appeared on the back of 18 album jackets from 1964-66, ranging from Stevie At The Beach and Marvin Gaye’s How Sweet It Is To Be Loved By You to Recorded Live: Motortown Revue In Paris and the Elgins’ Darling Baby – not to mention six albums by the Supremes. The prose is generally adult, admiring but not totally sycophantic, and only occasionally overwrought (“Rising in a somewhat parallel spiral, but dominated by their artistic creativity, the Supremes in their own way have reached unbelievable heights of acceptance and success”).

St. James’ factual lowpoint may have been on the Paris album, referencing “a fabulously successful tour of Great Britain” by Motown artists in 1965 (“packed houses and wild enthusiasm”). Considering the writer was a lawyer, he also tried too hard to be hip on Where Did Our Love Go (“an un-topable beat in a true rockin-blues groove”).

His notes also hinted at a familiarity with the inside of Hitsville U.S.A., its working environment and its employees – as they should have done, considering that “Scott St. James” was a pseudonym for a key member of Berry Gordy’s business team, legal administrator Ralph Seltzer. If his sleeve-note skills were common knowledge inside 2648 West Grand, that certainly wasn’t the case outside. Most Motown pilgrims had no idea until recording engineer Mike McLean explained, in a 2002 post on the Soulful Detroit website’s Motown Forum, how he discovered St. James’ identity.

“Mr. Seltzer was my boss,” wrote McLean, “and I spent quite a lot of time with him.” This led the engineer to recognise words and phrases frequently used by the lawyer in meetings, and which he noticed had often made their way into liners attributed to St. James. McLean found an intriguing way to have Seltzer admit his pen name, much to the lawyer’s amusement. Left unclear was why he wrote so many album notes: for enjoyment or reward, under instruction or voluntarily? (Without success, I tried to reach Selzter in Kerby, Oregon, when researching Motown: The Sound Of Young America. He would have had many interesting tales to tell.)

Can you spot the typo?

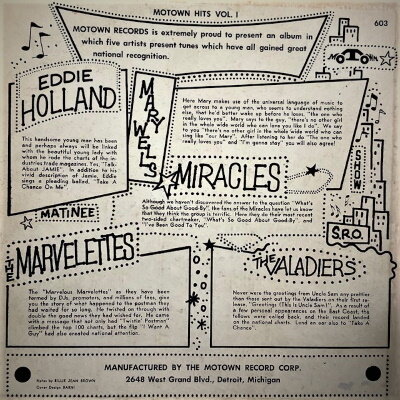

One or two other backroom believers did sleeve notes, including then-promotion director Barney Ales for the album Eddie Holland; publicist Al Abrams for the Marvelettes’ Please Mr. Postman; and songwriter Ron Miller for Recorded Live: The Motortown Revue Vol. 2. Another publicist, Ed Aaronoff, penned notes for LPs by Stevie Wonder (Up-Tight) and the Isley Brothers (This Old Heart Of Mine) before unexpectedly leaving the firm.

And the boss? The debut album by his first star, Marv Johnson, might have been the place for liners by Berry Gordy, but DJ Larry Dixon from WCHB Detroit took the task instead, perhaps in gratitude for past (or future) airplay. Gordy did add words of praise to one of his company’s 1962 releases. “Over the years, I have been associated with many great artists and it’s not easy for me to get excited,” ran the copy, “but I must admit that THE MIRACLES never cease to amaze me.” This was for the group’s third album, I’ll Try Something New.

Gordy repeated praise for his soul brother on The Temptations Sing Smokey in 1965. “[O]nce or twice in a lifetime someone comes along that had you not run across them,” he wrote, “your life would not have been as full and rewarding as that individual has made it.” After that, Motown’s founder seldom endorsed any artist’s LP in this manner, perhaps to avoid charges of favouritism. One exception (surprise, surprise) was Diana Ross & the Supremes’ Farewell boxed set in 1970: “Diana Ross will be a great star,” Gordy wrote in the accompanying booklet. “Mary Wilson, Cindy Birdsong and Jean Terrell will keep The Supremes supreme. Things will be different, but they’ll be the same. We’ll be together – still.”

Diana Ross’ own excursion into the world of liners, and those authored by some of the other stars named above, will follow next time in West Grand Blog. To close, here are a few others who were responsible for what you could read on a Motown LP cover, back when such things mattered:

Paul Drew. The Detroit-born disc jockey was the first to spin the Contours’ “Do You Love Me” on the radio after he paid a visit to Berry Gordy and was impressed by what he heard. “And I didn’t leave the office until I had a copy securely in my possession,” Drew later wrote in liners for the group’s album. He broke the record on influential Atlanta station WAKE, much to Barney Ales’ delight. “I was very particular about giving records to people ahead of release,” Ales told me. “But Paul was there – I had introduced him to Berry – so Berry played him ‘Do You Love Me,’ and Paul went nuts. Still, we had a deal that he wouldn’t play it until I could get the records ready to go, shipped and all that.”

Two years later, Drew was at top-rated WQXI in Atlanta, still spinning Motown hits – and still writing. “We were talking about records and Paul McCartney said there was a new song that really turned him on. He sang a few bars of it for me…and sure enough, it’s the very same song that’s been turning everyone on for the past couple of months, ‘Baby I Need Your Loving,’ by the Four Tops.” Logically enough, Drew told this story in sleeve notes for the quartet’s first Motown album.

One of those “sightless great artists”

Lee Ivory. The Detroit journalist was recruited by Motown in 1963 after it spotted his locally-published newspaper article about Stevie Wonder. His first liner notes proved more serious than most, for The Great March On Washington, the recording of Rev. Martin Luther King’s stirring civil-rights speech (“I have a dream”) in the nation’s capital in August 1963. An excerpt: “Truck convoys of Army troops swept across the city while citizens slept; combat-ready troops raced to take up strategic positions along the route of march as the dawn rose cool and clear; police, standing not more than five feet apart, prepared to encircle the periphery of the law-making area of the nation’s capital; while district police and national guardsmen were preparing to locate on practically every downtown corner. Washington D.C. was, indeed, prepared.”

Ivory’s subsequent Motown writing wasn’t as political, although the music of Marvin Gaye and Mary Wells had influence that politicians would envy. Ivory’s work included liners for those two singers’ respective Greatest Hits albums, for their Together duet set, and for Gaye’s When I’m Alone I Cry and Mary Wells Sings My Guy. After leaving Motown, he wrote for other newspapers and worked in TV in Chicago; Ivory also became publicly critical of what he saw as the company’s preferential treatment towards white journalists and broadcasters over their black counterparts.

Ragni Griffin. The Swedish-born journalist for Jet and Ebony penned the notes on Motown’s posthumously-issued The Prime of Shorty Long in 1969 – the year she married Junius Griffin, a significant figure in the firm’s relationships with the civil-rights and black militant movements. Among other duties, he managed artists’ participation in events supporting the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and co-produced an album by Stokely Carmichael. Ragni told me that Rev. Martin Luther King’s widow, Coretta, often relied on her late husband’s advice, “and she would make long phone calls to our house.” The opening track of The Prime of Shorty Long, “I Had A Dream,” took its theme from the oratory of Rev. King.

Ed Ochs. He was Billboard magazine’s R&B editor during the late 1960s and author of its widely-read Soul Sauce column, so an invitation to pen liners for Motown was no surprise. “I was still a mad poet then, fresh out of college and the Vietnam draft, yet to become a real writer,” he explained. His work appeared on such albums as Tammi Terrell’s Irresistible, Jr. Walker & the All Stars’ Home Cookin’ and Smokey Robinson & the Miracles Live!

“Smokey Robinson is a poet of the people,” declared Ochs’ copy on the last of those, “seen and heard in every city where soul is king and motion is a way of life. His stories can brain you, leaving only body.” Reminded of this and other examples, the Billboard veteran admitted, “It’s pretty embarrassing for me to see my young devil.”

Others may feel the same, 50 years on. That’s the trouble with words attached to physical media: someone, somewhere, still has a copy.

West Grand Blog is taking a short break. (You may need it, too, after the above epic.) See you on the other side, with luck.