A Bass Odyssey

‘YOU’LL NEVER BE ME, AND I’LL NEVER BE YOU’

For one brief, fabulous moment, father and son were on the charts simultaneously.

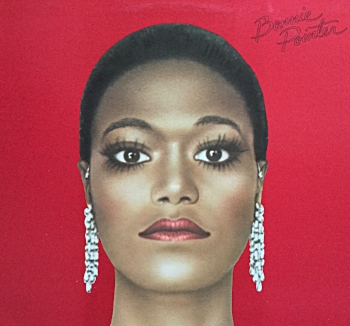

Climbing the top 50 of the Billboard album charts, rung by rung, was the debut by a new disco band on Ariola America Records. Further down, the first solo release on Motown by a sister from Oakland was making an entrance.

What connected them? James Jamerson, junior and senior, musicians both.

It was December 1978. The son was barely more than a teenager, one-half of a studio concoction called Chanson, whose single, “Don’t Hold Back,” was soon to reach the top 30 of the Billboard Hot 100. The father was a West Grand god, whose flowing bass was fuelling a couple of remakes (“Heaven Must Have Sent You,” “When I’m Gone”) on Bonnie Pointer’s eponymous album. As it happens, he had played on the originals of both songs.

James Jamerson Jr.

It’s intimidating – unnecessary, even – to write about Jamerson the elder. His work is revered to this day, his bass playing imaginative beyond reason or restriction. And his influence has previously been documented with passion, detail and colour in Allan Slutsky’s Standing in the Shadows of Motown, first as a book, then as a movie.

Besides, words will always fall short of explaining Jamerson’s alchemy, whether on “Bernadette” or “I Was Made To Love Her” or “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” or…

For another assignment, I needed to listen to Bonnie Pointer’s “Heaven Must Have Sent You.” It took but seconds to be back under Jamerson’s spell, even when cast so late in his career. Then curiosity prevailed, and I remembered that Bonnie’s album was recorded in the same year that Chanson cut their one and only hit.

“Don’t Hold Back” was no masterpiece, no “…Made To Love Her,” no “…Mountain High Enough,” but it married a magnificent groove to a great hook. Chanson had its moment, standing proud, while making clear that the apple had not fallen far from the tree.

Tragedy unites the two Jamersons, of course. The father died in 1983 at the age of 47, the son in 2016 at the age of 58. There’s a poignant story in Slutsky’s book, relating how both musicians were accidentally booked on the same recording session in Los Angeles. “When they met at the studio and realized what had happened,” he wrote, “James tearfully hugged his son and said, ‘Go in there and kick ass.’”

That’s what Jamerson Jr. did for much of his professional life, working with all sorts of stars – Andrae Crouch, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Natalie Cole, Luciano Pavarotti, Chaka Khan, the Mighty Clouds of Joy – as well as a cavalcade of Motown acts in Los Angeles. Just a few months before Chanson’s breakthrough, for example, Jamerson was playing bass behind Smokey Robinson at the Roxy, for the show which produced the singer/songwriter’s Smokin’ album.

Another remarkable bassist, Allen McGrier, grew up with Jamerson the younger, “when we were both in the seventh grade in Detroit,” he told Slutsky. “We had several music courses together, so I always knew that Jamerson Jr. was a great bass player.” But McGrier didn’t know about his friend’s father “until one day in our eighth grade talent show. A few of the parents and teachers got up to jam, and Jamerson Sr. – we called him Pops – brought down the house. I mean, he jammed.”

Bonnie Pointer: heaven sent

According to McGrier, Jamerson Jr. finished school in Detroit, “and we always talked about playing on the same records.” The opportunity came after both men had moved to Los Angeles, where McGrier was working with Teena Marie for Epic Records. “We had cut all the tracks for Teena’s upcoming album” – this was Starchild – “and we weren’t quite happy with one of the bass tracks.

“So I suggested to Teena that we call in James Jr. on upright. She agreed, and James Jr. and Pops came into the studio later that evening, with the same upright Pops had played on all the early Motown hits. It was great, I mean, it was fantastic.”

The son was six years old when that upright’s sound resonated on Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” Motown’s first international smash. “When I was growing up in Detroit…I spent a lot of time watching my dad cut all those hits,” he told Slutsky. “At that time, being a kid, I was more interested in the hamburgers that the producers brought into the studio than in the music they were playing.”

Jamerson added, “Learning to make the connection between my soul and my instrument came from checking out what my dad, and the rest of the musicians my dad called the Funk Brothers, were doing. Very few musicians got the opportunity to learn like this, so I considered myself very blessed. Dad always told me, ‘You’ll never be me, and I’ll never be you, so just be yourself and play what you feel. If you don’t feel it, don’t play it.’”

Being himself brought Jamerson Jr. consistent work in the recording studio and on the road, as well as the company of other unique players. One project put him together with guitarists David T. Walker, Eric Gale, Phil Upchurch and Wah Wah Watson, and drummer James Gadson. The sextet played material from the Jobete catalogue, and an original by Ali “Ollie” Woodson, the onetime Temptation who sang on several tracks. The resulting album, Spirit Traveler, was released in 1993.

“Junior had a good career as a studio musician,” Allan Slutsky told me the other day, “but he always lived in his father’s inescapable shadow. It was tough on him, even though he deeply loved his dad.”

Ten years after the release of the movie Standing in the Shadows of Motown, Slutsky created a multi-media concert tour with the same name, with a band featuring Jamerson Jr., singers Peabo Bryson and Leela James, scripted narration (“Welcome to the Snakepit!”) and projected images of Jamerson Sr.

Jamerson Jr. and friends on the road

Jamerson Jr. even did some interviews around the tour, talking about the music. Of “Bernadette,” he explained to Sarah Rodman in the Boston Globe, “I think that’s more of a bass player’s song. The bass line was difficult for me to play even, because [my father] was all over the place.” Of “I Was Made To Love Her,” Jamerson said, “So many people have tried to claim they played bass on that song. No, it’s dad.” And of “What’s Going On,” he remembered, “The funny part about that one is [my father] was a little inebriated and he played that song on his back because he couldn’t sit on his stool.”

The roadshow was booked into venues in a half-dozen states in the northeast U.S. during March 2013, plus the celebrated Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C. “We played two dozen Motown tunes,” recalled Slutsky. “The band was incredible, formed from the guys I played with on the musical The Color Purple, and some friends from Philly.”

Despite the creative concept and the calibre of musicianship – not to mention the earlier success of the movie – the tour struggled to draw crowds, admitted Slutsky. “Junior was really down and out, but played very well and was in his final period of some glory. He loved the hang in the tour bus.”

Jamerson Jr. also suffered from poor health, a degenerative spinal condition which, said Slutsky, “left him looking like a gnarled birch tree.” He died on March 23, 2016 in Detroit, with a public viewing at the James H. Cole Funeral Home on West Grand Boulevard – immediately next to the original Motown headquarters.

In 1978, when “Don’t Hold Back” was heading for chart heights, the father displayed no jealousy. “He couldn’t have been prouder,” said Jamerson Jr. during the 2013 tour. “I learned that in the summer of 1983, when he had to be hospitalised after a heart attack. He told me how happy he was, seeing what I’d accomplished, and he wanted me to have his upright bass. It meant the world to me, but at the same time, it broke my heart. He was giving me the bass because he knew he wasn’t going to make it.”

Music notes: both albums by Chanson are available on streaming services, as is Bonnie Pointer’s “Heaven Must Have Sent You” in versions released both as a seven-inch single and as a 12-inch (the latter is bundled into a Pointer Sisters hits compilation). A later permutation of “Heaven” was Motown’s first digitally-recorded track, distributed as a 12-inch disco single in 1979. Neither of Pointer’s Motown albums are available digitally as far as I can tell. In 2012, Big Break Records reissued Bonnie’s first album on compact disc, containing “Heaven” thrice – the album, single and digitally-recorded versions. Smokey Robinson’s Smokin’ can be found on streaming services; Spirit Traveler cannot. And, of course, much of the senior Jamerson’s work is digitally accessible, including the isolated bass line of “Bernadette,” contained in an abridged soundtrack of Standing in the Shadows of Motown.