Ageless, the ‘Book’ of Wonder

ALWAYS LOOKIN’ FOR ANOTHER PURE LOVE

Stevie Wonder’s monumental Talking Book was released on this date in 1972. But, originally, there was a different plan for the music. “Because we had all those songs,” Malcolm Cecil recalled thinking at the time, “instead of putting out an album, why don’t we put out a book of singles?”

Motown Records was adapting to new ways of working with Wonder – not yet a superstar, although speeding in that direction – since granting unprecedented creative control to him in the contract signed in 1971, after he turned twenty-one. But a book of singles?

“I thought it was a wonderful idea,” said Cecil. “Anyway, they wouldn’t go for it.” The British musician was a key member of the crew around the adult Wonder as he created a tsunami of new music which swept the world from ’72 onwards: Music Of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions and Fulfillingness’ First Finale.

Stevie played most of the instruments on those life-changing, superstar-making albums, and produced them himself. His technology mentors were Malcolm Cecil and fellow studio whiz Bob Margouleff, who together helped him to explore and master the groundbreaking Moog and ARP synthesisers. The two men were acknowledged as associate producers of the albums, and also credited for their engineering and programming skills. Both graciously granted me interviews years ago, and what follows is drawn from those recollections. With luck, it will not be overly familiar to you on this anniversary.

With Motown nixing the book-of-singles concept, Team Wonder considered other ways of making a splash. “We finally said, ‘We want two strong singles – we’re going to head off each side [of the album] with a strong single,’ ” stated Cecil. These were “You Are The Sunshine Of My Life” and “Superstition,” and the latter was the first 45, released three days before the record company shipped Talking Book.

The details shown in the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) paperwork for “Superstition” are simple enough. The studio was New York’s Electric Lady on West 8th Street, the date was May 26, 1972, and the hours booked were 2:00pm to 5:00pm. The “employer” was Kee-Won Records (Gene Kee was Wonder’s musical director). The contracted sidemen were Trevor Lawrence on sax and Steve Madaio on trumpet, who earned union scale of $99 apiece for the date. As noted above, Wonder played all the keyboards – layered as they were – as well as the drums which ignite the track at its start.

History has since shown that “Superstition” was anything but simple. What turned out to be Stevie’s first crossover No. 1 since “Fingertips – Pt. 2” had initial connections to London, where Cecil, Wonder and Kee had gone in February 1972. “I wanted to use British string players,” said Cecil, “because the strings sound very different in the States. In Hollywood, they were very scratchy, and in New York, there weren’t really any string sections left, because they had disbanded. I said to Stevie, ‘To get a really sweet sound, I keep hearing the sound of the [BBC] radio orchestra I used to work with – let’s go to London and do it.’ ”

After they did just that at the city’s AIR Studios, “then came the parade, one at a time,” Cecil explained. The visitors included Jeff Beck, Calvin “Fuzzy” Samuels and Eric Clapton. “The word went around, obviously: ‘Stevie is in town and he is receiving.’ Everybody came over to play and to talk, and to have fun. That’s how we met Jeff.” Wonder was impressed by Beck, and the guitarist got to hear a new song Stevie had begun writing in London, “Maybe Your Baby.” He was invited to New York.

By Cecil’s account, Beck was sufficiently taken by that song to seek it for his own album with Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice, which Cecil and Margouleff were also producing that summer. But Wonder wanted “Maybe Your Baby” for himself, and promised something else to the British musician.

And so runs another well-oiled story: how Wonder at first gave an incomplete “Superstition” to Beck, changed his mind after hearing what he did with the song, and chose to keep it for himself. An alternative account is that Berry Gordy refused to allow “Superstition” to go to Beck, believing it to be a potential Wonder smash. It’s difficult to know the exact circumstances, beyond the fact that Stevie made at least one recording of the number in May (as per the AFM contract) and that, according to an Electric Lady Studios log, Beck taped the same song – or some part of it – on July 1. “Then,” said Malcolm Cecil, “we used the original version that Stevie had [recorded]. He wanted to cut the vocal, and we finished up Talking Book.”

Cecil advised me that Jeff’s original “Superstition” was under lock and key. “We still have the master, absolutely. Stevie told me that if I put that master out, he would have my nuts on the wall.” Beck did do a second version, but it was not released until halfway through the following year on the Beck Bogert Appice album.

Trade press advert for Talking Book

Wonder and his team had other preoccupations in the summer of ’72, not least touring North America as opening act for the Rolling Stones (for more on that two-month trek, see here). The first date? Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum on June 3. The previous night, a little further south, Wonder was booked into Hollywood’s Crystal Sound Studios from 10:30pm to 3:00am, putting “Maybe Your Baby” on tape, with Detroit guitar prodigy Ray Parker Jr. – at age eighteen! – adding parts. Ten days later, between concerts in Los Angeles and San Diego, Wonder was back at Crystal Sound, cutting “Tuesday Heartbreak” with the help of saxman David Sanborn.

During the rest of June and July, studio sessions gave way to rolling with the Stones, although a number of those shows were recorded for a live album set (it was never released). Audiences across the country received a Talking Book preview when Stevie included a show-stopping “Superstition” in his setlist. The tour finished at New York’s Madison Square Garden on July 26. Eight days on, he was back with Cecil and Margouleff at Electric Lady, finalising “Lookin’ For Another Pure Love” with guitarist Howard “Buzzy” Feiten.

Later in August, Wonder cut more material at the Record Plant in Los Angeles. After every new song, Cecil and Margouleff would ask whether it was intended for the album. “Yes” was always the answer. “So finally we had about thirty songs,” Cecil remembered, “and I said, ‘Stevie, this is an album, not a talking book.’ That’s how the title came about.

“We spent a lot of time figuring out what would work after what song, and what tempos would work, and blending them together – such as the mixing of ‘Superstition’ into ‘Big Brother.’ They are almost the same tempo, but not quite. We spent a lot of time getting that cross-fade right, so the compilation of the album was a really important part to us.”

To choose ten songs from so many was evidently a challenge. One track laid down that August, “Don’t You Worry ’Bout A Thing,” had to wait to be drafted – into Innervisions, one year later. Other material from the 1972 sessions remained in the vault, such as “The Future” and “Papa Do.”

Cash Box chart of w/e January 20, 1973

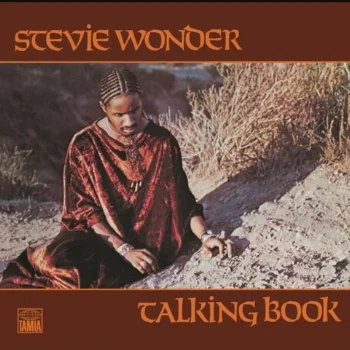

As the album’s October release date approached, other components had to be assembled, including the album jacket design. Bob Margouleff was an experienced photographer, in addition to his synthesiser programming and engineering skills, and it was he who shot the Talking Book images, including the front cover. “Stevie without glasses in that very biblical setting was all part of it,” said Cecil.

Now there was another demand made of Motown: to use braille on the LP sleeve. This time, the record company acceded, for first pressings, anyway. “Motown was upset,” Cecil explained, “because [it meant] they were only going to get 20 instead of 25 records in a box. We had to use heavier card stock to get the braille in.” The tactile message read, “Here is my music. It is all I have to tell you how I feel. Know that your love keeps my love strong. Stevie.”

Whether in visual, musical or spiritual terms, Talking Book revealed much about a maturing Wonder at age 22. Music Of My Mind had caught critics’ attention; now, they were all ears, exemplified by the five-star review in Rolling Stone. Moreover, Stevie’s tour with the Stones had been the perfect set-up with the music-buying public. And so it was that, upon first release, the album sold more than 1.5 million copies in the U.S., reaching the Top 3 of the Billboard charts and spending more than two years there. Both “Superstition” and “You Are The Sunshine Of My Life” were No. 1 singles, as satisfying a result as the Wonderers could have hoped for. And both hits also earned Stevie his first Grammys, the start of a haul which grew to a dozen such statuettes across four albums in the 1970s.

Thus began the gospel of Wonder, complete with biblical setting.