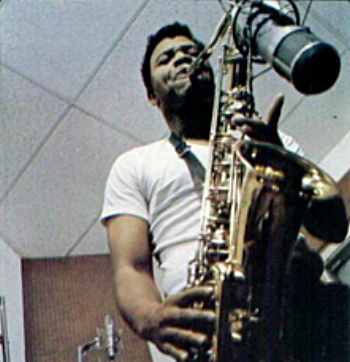

Blow the house down, Junior

From juke joints to halls of fame

Witnesses told police they heard a gunshot. True or not, the victim of the attempted murder, Arthur Joiner, certainly received a gash on his forehead when he was struck down on the steps of the El Grotto Lounge, 65 years ago this week.

“It was affectionately known as the Bloody Corner,” said Johnny Bristol, “because somebody got bloody every weekend. Except us, thank God.” The late Motown songwriter/producer was recalling the nightclub where he and singing partner Jackey Beavers used to perform at the dawn of the 1960s. Fist fights and brawls were common; once, a triple shooting involved the bar’s doorman.

Welcome to Battle Creek, Michigan, about 120 miles west of Detroit, and to the city's notorious El Grotto at South Kendall Street and Hamblin Avenue, where Johnny & Jackey, Al Green, Wade Flemons and the Dells, among others, once played. The lounge also presented burlesque shows, and sometimes the girls did snake dances. With live snakes.

Oh, and Jr. Walker & the All Stars were the club’s resident band. “They were excellent,” Bristol told me. “The place was constantly packed. The lady raised her cover charge from 50 cents to a dollar. It was incredible. Jr. could play the blues, he could play jazz, rock and definitely soul.”

The lady was Helen Montgomery, co-owner of the El Grotto (capacity: 300 souls) with husband Robert, and an active figure in local community life. “I was like a son to her,” Walker told the Battle Creek Enquirer in 1992, three years before his death at age 64. “Anytime I needed money, she would always give me some. I remember she helped me buy a 1957 Buick. She was always saying, ‘Junior – you spend too much money.’ ”

If Helen Montgomery was familiar with Walker, Johnny Bristol was familiar with his musicianship, and perhaps more so than anyone else, since Battle Creek had brought them together. The Arkansas-born saxophone wizard – you can’t call him a sax player, because that word falls way short in descriptive duty – had landed his first gig in the city through his band’s drummer. Bristol, for his part, was in the U.S. Air Force, stationed at nearby Fort Custer, but with ambitions in music. As members of the High Fives, he and Jackey Beavers sang in local clubs. “Jackey and I took it more seriously than the other guys,” he said. “They [only] needed half a gallon of wine.”

The pair’s ambition eventually brought them into contact with Billy Davis and Gwen Gordy’s Anna Records, and later with Harvey Fuqua, Gwen’s husband. Johnny & Jackey recorded for Anna, and for Fuqua’s Tri-Phi label. No surprise, then, that Bristol should enlist Junior into this circle. His first 45 on Tri-Phi followed in early 1962. When Harvey sold his business to Berry Gordy in 1963, Walker became wedded to Motown.

The resulting records were, of course, wonderful – gritty, rockin’ and (mostly) raw – and you know well the chronology and the commerce: “Shotgun,” “Shake And Fingerpop,” “(I’m A) Road Runner,” “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You),” “What Does It Take (To Win Your Love)” and more, accumulating a total of thirteen Billboard Top 10 R&B hits between 1965 and 1972. Not to mention honours from the Grammy Hall of Fame and the Rhythm & Blues Foundation, plus that improbable pop-up solo in Foreigner’s “Urgent" in 1981.

Junior Walker and his All Stars: Vic Thomas, Willie Woods, James Graves

But, in retrospect, what intrigued me most about Walker was his nonchalance. Not for him Marvin Gaye’s anguish, or David Ruffin’s ego. He just seemed to want to make music and money, preferably on the road, paid in cash. It’s the Chuck Berry business model, if anything, without the underage girls.

“He liked being in the studio, but the road always came first,” explained Lamont Dozier, who co-produced “(I’m A) Road Runner” and more. “He had about twelve kids, man, he needed the work. I guess he figured being in the recording studio was a gamble. He needed to be out there, picking up the money. It’s a sure thing, right? He could see it in his hand, [instead of] waiting six months for a royalty cheque.”

Johnny Bristol agreed. “I had studio time set up for Junior, and [I was] sitting there, waiting, and he would call me from Indiana and say, ‘Look, I had to call you, man, ’cause this guy called me at the last minute, and I have to go make this money. I’ll be there tomorrow, can you set it up for tomorrow?’ ‘Yes, Junior, OK.’ ”

This cash-call priority may even have resonated with Berry Gordy. Something evidently did, because the boss produced (or co-produced with Lawrence Horn) a notable number of Walker’s 1964-65 sessions. And he did so despite the increasing preoccupations and pressures of Motown business. Among Gordy's productions for Junior: “Shotgun,” “Monkey Jump,” “Satan’s Blues,” “Shake And Fingerpop” and “Shoot Your Shot.”

“His saxophone sound was like nobody else’s,” Gordy wrote in his autobiography. “The down-home feeling he and his band got when he sang and played his horn made it easy to produce him. All we had to do was get a good sound balance in the studio and just wait.”

“All we had to do”? Not if you believe Earl Van Dyke, who told me that Gordy caught an early version of “Shotgun” and “went ape. He heard it, he felt it – but then he said, ‘Well, it’s got to be cleaned up,’ because Junior had tried to cut it with his group. Berry said, ‘We can’t put that out,’ so he had to infiltrate staff musicians into Junior’s band. That’s Benny Benjamin on drums and James Jamerson on bass.”

Van Dyke added that on “Shotgun,” he had to dub over the guitar of the All Stars’ Vic Thomas with the fretwork of session pros Joe Messina and Eddie Willis. Ultimately, such a switch-up didn’t matter. The record was a five-alarm R&B and pop smash – the band’s first – and it fired up their booking fees.

“Junior’s guys were basically a road band,” Johnny Bristol remembered. “I’m sure they could be recorded in the studio, but it was a lot more expedient and professional to use guys at the company, Earl Van Dyke, James and so on.” When Bristol and Harvey Fuqua produced Walker & the All Stars’ “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)” in the spring of 1966, they cut the basic track first, “then we went in and did the vocals, and then added the sax.”

By Lamont Dozier’s account, Walker didn’t even like to sing. “He just didn’t believe in himself. He liked to sing little riffs or something while he was playing the sax, and he would holler out something like ‘Shotgun.’ But when he had to sing ‘(I’m A) Road Runner,’ it took some skill vocally, and he just didn’t feel he was up for that. But he pulled it off.”

That’s an understatement. Junior pulled off “(I'm A) Road Runner” and then some. In fact, he recorded sufficient material for more than 15 Motown albums to be released during his working life. The biggest seller? Greatest Hits, issued in 1969. The best retrospective? Nothin' But Soul: The Singles 1962-1983, released in 1994.

So Jr. Walker & the All Stars have stood time’s test, and have obviously influenced others, too. In 1990, Jobete Music sued Steve Winwood, contending that the British musician’s “Roll With It” substantially infringed the copyright of “(I’m A) Road Runner.” Eventually, the claim was settled, to Jobete’s advantage.

“Shoot ’em ’fore he run now!”