Rick to the Rescue

‘STREET SONGS’ CONTINUES TO BE SEEN AND HEARD

Forty years ago, Motown Records needed what Rick James delivered.

With his album Street Songs, the punk-funk star generated around $10 million for the company in 1981 – which may have been as much as 20 percent of its U.S. revenues that year. The income helped to offset the firm’s financial deficit from the late 1970s, which was Jay Lasker’s challenge as its new president. Not only was Street Songs certified platinum for one million copies moved within three months of release, but also its biggest hit single, “Super Freak,” sold some 900,000 units domestically, despite not cracking the Top 10 of the pop charts.

Perhaps more than money, James’ success was a morale-booster for all at Motown: evidence that it could adapt and prosper in a new decade, amid a music industry quite different to the one it had conquered and reshaped 15 years earlier. And the Buffalo cowboy did so with his look as much as his music – a creative asset which Motown understood and had shrewdly exploited with its earlier stars.

Photographer Ron Slenzak’s classic cover shot

Nothing captured James’ devil-may-care image and attitude – not to mention his lasciviousness – more than the promotional videoclips for the Street Songs singles. That they still have currency today is confirmed by YouTube stats: 94 million views to date for “Super Freak” (recently upgraded to HD quality) and 31 million for “Give It To Me Baby.”

That visual appeal is undoubtedly why there have been several attempts to capture the late musician’s turbulent life on film, including screenwriter Sheldon Turner’s Super Freak, announced in 2006, and filmmaker Addison Henderson’s My Brother’s Keeper, revealed last autumn. The former was never made, the latter is said to begin production this year, with the involvement of James’ brother, LeRoi Johnson. In addition, a new TV documentary about the Motown star is due soon from the Showtime network.

So far, the 40th anniversary of Street Songs (it was released on April 7, 1981) hasn’t yielded much media attention, aside from this PopMatters essay. That Rick James died as the result of his own addictions, rather than, say, by a father’s hand, may have something to do with it. That the album’s biggest hits were unashamedly about sex, rather than the woes of mankind as woven into What’s Going On, may also explain it. But those YouTube numbers…

NEW SCHOOL vs. OLD SCHOOL

The videoclips for “Super Freak” and “Give It To Me Baby” were made in 1981 under the jurisdiction of Nancy Leiviska, when she was Motown’s vice president of video production. So was the filming of James’ high-voltage concert at California’s Long Beach Arena in July 1981, originally intended for home video release and/or broadcast via cable television. Leiviska was one of the record industry’s pioneering music video executives, finding her way – and Motown’s – as the medium became important, then mandatory, as a means of marketing music. She did this despite Jay Lasker’s lack of enthusiasm for videoclips, as she recalled for me earlier this month. “Jay was telling me, ‘We’ve got to put you somewhere else [in the company], Nancy.’ He didn’t want to spend the money, he’d rather buy full-page ads in the radio trades. He was old school, believing that radio sold records.”

Motown had another problem in navigating the new landscape. The primary music video platform in the U.S. during the 1980s was MTV, and its self-proclaimed format was rock, a disingenuous programming decision which effectively shut out black artists, including Rick James – who had with Street Songs the third biggest-selling album in the nation on the day that MTV began broadcasting: August 1, 1981.

Nancy Leiviska directs the punk-funk king

Three months later, during a Billboard music video conference, Leiviska was asked about MTV’s impact on Motown’s sales. “How would I know?” she said. “Rick James has sold six million albums and MTV won’t accept his promotion films, or those of superstars like Diana Ross or Lionel Richie, either.” Today, she vividly recalls James’ reaction. “Rick would start calling me, ‘You’ve got to get me on MTV!’ He was screaming and shouting.”

What helped Leiviska to calm the star was prior acquaintance. “I’d known Rick since 1969,” she says. “I knew him as James Johnson, then as Ricky Matthews with White Cane. He wrote in two of his books that he was a secret fan of mine. In ‘Ghetto Life,’ he mentions my name – but I never had a romantic relationship with him.”

At the time of his first R&B chart-topper, “You And I,” Motown’s video department didn’t exist. It was created in early ’79 with Leiviska in charge, although James’ sole R&B Top 10 hit that year, “Bustin’ Out,” was outsourced to Videography Studios, a local production firm. She also remembers voicing a radio commercial for the album. “Rick didn’t like any of the male voices they used, he wanted a girl. That’s why you hear me in the national spot saying that Prince will be opening up for Rick on tour. And I had to join the voiceovers’ AFTRA union.”

‘GET THOSE EXTRAS OUT!’

The first clip that Leiviska recalls directing was for “Don’t Look Back” by Teena Marie. “We went down to the beach at Santa Monica. Teena showed up with a broken leg, so I had to use Jill Jones, Fuller Gordy’s stepdaughter, to shoot the bottom of her leg, walking through the sand.”

By the time of Street Songs, director Nick Saxton was working with Motown, and he handled the clips for “Give It To Me Baby” and “Super Freak.” Leiviska says, “We rented a house in Trousdale for the first of those. We made a living room look like it was a club scene, and then there was the jacuzzi.” The second clip was filmed at A&M Records. “I’m in ‘Super Freak,’ because we had to have a bunch of our own people do the choruses. Rick was so high that we had to let the extras go. ‘Get them out of here!’ Terry Gordy and his wife, attorney Desiree Gordy, are in the video, too.”

An informal moment: Nancy and Rick, circa 1979

James’ drug habit also afflicted the clip made for the Temptations’ “Standing On The Top,” which he wrote and produced. “I had to call Berry, because Rick was really out of control. He would complain that artists at all the other record companies had cocaine budgets, how come he didn’t? I had to tell him that wasn’t our policy. I remember him yelling, ‘You’re just that little flower girl I knew in the ’60s, you don’t tell me what to do.’ ” Back then, he was this cool guy who didn’t really get high, but now I’m elevated to a different position, and so is he – but we still think of ourselves as these ’60s kids. That was a problem with us. I had no time for his shenanigans.”

The call to Gordy saw the boss come to the shoot. “We’re videotaping the Temptations, we’ve got the truck outside. We went into the truck, there were a couple of people there. Rick lit up his joint in front of Berry, and we were all going, ‘What is he doing?’ He’s trying to pass it to someone, and Berry whispers in his ear. All of a sudden, Rick starts laughing.

“It was this great little lesson Berry taught me about a problem like that: when you’re with the artist, take them aside, keep it private, especially if they’re high. Rick put the joint out. We thought they were telling jokes. What Berry really said to him was, ‘If you don’t put that fucking joint out and show me some respect…’ ”

The summer before, the shoot of James’ two-night concert in Long Beach had gone without incident. Motown executive Lee Young was in charge of the budget, by Leiviska’s account, but it was only approved the night before. “I said, ‘I can get us a laserdisc deal, but we’ve got to show them we can do it. We had a crew, a truck, five cameras – everything for $30,000. Filming was done on the second night, and it was a great concert, but it seemed that Rick never really wanted to go in for the video release.” The post-production never took place – and the film tapes were subsequently, and inexplicably, lost.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE DREAM?

Rick James never regained the heights achieved with Street Songs and its attendant concert tour in 1981, which was seen by more than 250,000 fans and grossed in excess of $2 million in ticket sales (equivalent to more than $6 million today). “What happened to him was a tragedy,” says Leiviska. “He was very astute, very smart – he could have run the company’s A&R department, or have been its president one day. I used to say to him: ‘What happened to the dream that you were going to run Motown? No one believes you now.’ When he got on drugs…” Leiviska doesn’t finish the sentence.

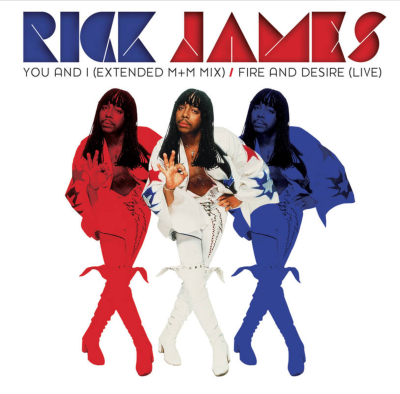

For Record Store Day 2014

“He was a fighter, and he really loved Motown,” declared Jay Lasker, years later. “He had more of a feeling for helping the perpetuation and success of Motown than any of the [other] artists.” James himself, speaking to Billboard as Street Songs was hitting its sales stride, cited the company’s heritage. “One of the great things about Motown,” he said, “was the family relationships between the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations and the other acts. We’re trying to get that back.”

That there was depth to the extrovert James, thoughtfulness as well as outrageousness, may be why his story continues to attract filmmakers. Actually, movie producer Jerry Weintraub was interested during the ’80s: there was a quasi-autobiographical project, The Spice of Life, touted in the media, with the singer claiming that screenwriter Richard (Let’s Do It Again) Wesley was involved, together with Motown Productions. It came to naught.

The Tribeca Film Festival in New York this June will see the premiere of Bitchin’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James, co-written and directed by a former music editor of Vibe magazine, Sacha Jenkins, and produced by Steve Rivo. Thereafter, the documentary about this “complicated and rebellious soul” will be seen on Showtime. Naturally enough, Nancy Leiviska was interviewed, as was another rebellious soul of music and film, Ice Cube. “Street Songs is kind of like the first gangster record,” the rapper/actor said a while back. “I felt like he was talking to me. It was the most hard-core record you could get at the time.”

Judging by those words, it wasn’t just Motown that needed what Rick James delivered 40 years ago.

Music notes: if that long has passed since the original release of Street Songs, it’s 20 since the album’s reissue in a 2CD deluxe edition. The latter was notable for adding 75 minutes-plus of Rick James’ Long Beach Arena concerts, including star turns by Teena Marie. Today, this deluxe Street Songs is available on streaming services. So is 2011’s expanded edition of Teena’s Irons In The Fire album, which contained a previously-unissued version of “I Need Your Lovin’” from Long Beach. Another transcendent performance from those shows was Rick and Teena’s “Fire And Desire,” but that particular segment was lost for years. It finally emerged on Record Store Day in 2014 as a vinyl 12-inch, the cover of which is illustrated above. And if your interest in Street Songs extends to samples, then you can, of course, start with M.C. Hammer’s Grammy-winning “U Can’t Touch This.”